| architecture |

| calligraphy |

| ceramics |

| clothing |

| comics |

| gardens |

| lacquerwork |

| literature |

| movies |

| music |

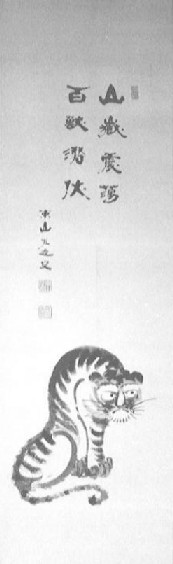

| painting |

| poetry |

| sculpture |

| tea ceremony |

| television |

| theatre |

| weaponry |

| thematic routes |

| timeline |

| the site |

context: thematic routes

Zen

Since the links to the right, expanding on or illustrating the comments here, can go to anywhere on the site (sometimes to whole sections with dozens of pages) they each open in a new window, so that this page can be retained as master context when you have finished exploring. |

|||

Zen the Religion |

|||

I have no interest in or knowledge of the Buddha-nature. I am an art fan. I knew very little of Zen before starting this work, just a vague notion of it not thinking much about deities, and being admired or revered by mostly stupid hippies. After reading a bunch of books, I have been able to properly develop the same kind of deep contempt I feel for other religions that I already knew well, particularly for its 'Ahhhh, do you see? Do you?' annoying koans and its official certificates of enlightenment. I don't think this is a problem, for the most part: I feel the same way about Christianity, and it doesn't stop me loving Bernini's sculture 'Ecstacy of St Teresa' or The Caravans' recording of 'Walk Around Heaven All Day'. |

|||

I wrote the above some time ago, and while I wouldn't recant, I think I should make this addition. The account of Zen that Zen offers is such that someone like me couldn't hope to understand it. Not just because I was brought up in a different tradition - Western, christian - but because I am very much a rationalist, someone with a particularly logical mind, probably fatally short of the kind of intuitive insight that Zen seems to require. I love much Zen art, but you may reasonably conclude that I am hopelessly unable to grasp Zen itself, and therefore you may sensibly choose to ignore my cynical, dismissive attitude to it. |

|||

Origins |

|||

Chan Buddhism appeared in China, thanks to the Indian monk known as Dharma (Daruma in Japan), something like 600 years before its transmission to Japan by Eisai in about 1191 A.D., where it became known as Zen. It differed greatly from the Buddhism that had dominated Japan for the last several centuries in its focus on meditation, backed with discipline and hard work, to unlock the truths of the universe, to achieve enlightenment. There were two branches in the early days: the rinzai branch believed in sudden flashes of enlightenment, and this was popular within military and artistic circles, while the soto branch preached slow growth in understanding, and was strong in rural areas. These came from Southern and Northern China respectively, but this doesn't appear to have fed into the Chinese artistic preferences of its adherents. |

timeline | ||

Aesthetics |

|||

The aesthetics of Zen are a rich area, treated at length elsewhere, so here I will just offer a list of the key qualities you expect to see in Zen art: asymmetry; simplicity; astringency; naturalness; subtle depth; freedom of thought; tranquility. In addition, a overtones of sadness, poverty and age are preferred. |

Zen aesthetics | ||

This doesn't address why their art is different, so some explanation is needed of what Zen is. It's a branch of Buddhism that does not interest itself in worshipping the Buddha at all, but instead in grasping the Buddha-nature in and underlying and uniting the phenomenal world. Zen art is about capturing the true nature of things, the inner soul - thus there is no real attempt at any kind of illusionism or realism. Also relevant here may be the abstraction of props and sets and physical movements in noh theatre. |

realism in painting | ||

Zen and Nature Zen seems to be at the heart of the Japanese relationship with nature. I was very struck by Suzuki's shock at mountain-climbing being expressed in terms such as "conquering" the mountain - he finds this an inconceivably alien way of relating to nature, as an enemy to be defeated. This difference may also explain why, as far as I know, the landscape as an artistic genre started earlier in the Zen countries than anywhere else in the world, and always remained a major genre. It may also explain why there are so many more depictions of plants, birds, animals and so on. In 'The East and the West: A Study of their psychic and cultural characteristics', Sidney Lewis Gulick says this: "To Occidentals, the physical world was an objective reality--to be analyzed, used, mastered. To Orientals, on the contrary, it was a realm of beauty to be admired, but also of mystery and illusion to be pictured by poets, explained by mythmakers, and mollified by priestly incantations. Suzuki takes what I think is a step further, and suggests that Oriental art depicts spirit, while Western art depicts form. One other note to make here is about the fact that while there is interest in depicting things suggesting eternity - mountains, gnarled and ancient trees - there is an even greater interest in representing change: scrolls that show seasonal changes, haiku on short-lived plants or creatures, haiku indeed capturing an instant, even the love of the cherry blossoms for several days each spring. The continuing flow and change of the real world is of central importance to the philosophy of Zen, even its epistemology, if we can use such terms of a religion opposed to logic and knowledge, and central to the Japanese people. |

haiku | ||

Zen and other ideas |

|||

Zen in Japan is not wholly separable from other strands of thought - Buddhism came from India, was altered in various ways by the Chinese, and further by the Japanese, and Zen is one of the results of this. Also, when it came from China, right at the start of the Kamakura period, it was accompanied by scholars and books centred around Taoism and Confucianism too - and all this has mixed in with Japan's native Shinto religion. It's beyond me to disentangle all this (even Suzuki often barely tries, flowing into Tao particularly as he pleases), but suffice to say that while we can say a lot of things specifically about Zen, there is much overlap, and many of its monks and priests had much more in their ideas than Zen alone. |

|||

Miscellaneous |

|||

There is much else to say about zen, in its relationship to painting, the tea ceremony, garden design, ceramics and so on, but since most artforms have or will have their own Zen-related section, those should be explored there. It is worth, I think, making one comic-book digression here. I give some reasons in the comic section as to why I believe the history of Zen art has been a crucial factor in making comics so vastly successful in Japan; this of course is not to claim that comics are Zen art, and most have nothing at all to tell us about Zen. Here I want to highlight and point you to one extraordinary story, by Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima in a magnificent series called Lone Wolf And Cub, which I think expresses some fascinating aspects of Zen in extremely powerful form, and is worth reading about, or indeed actually reading, before proceeding to the other chapter in this section. |

Zen painting (large section) tea ceremony section tea gardens section tea ceremony ceramics section Zen dry gardens section Zen calligraphy section Zen and comics a Lone Wolf & Cub story | ||

Zen and Samurai |

|||

sources |