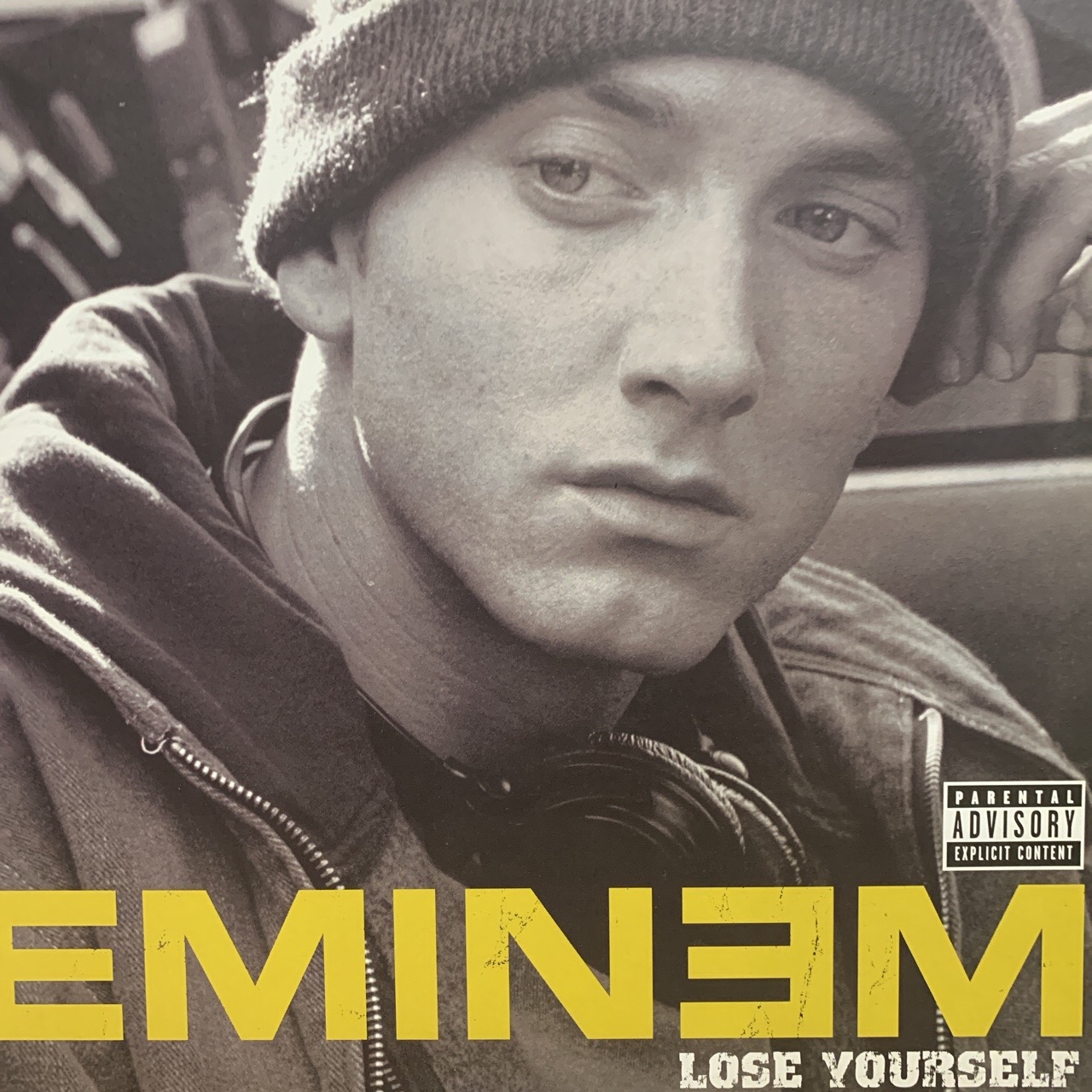

There’s a convention in DC Comics – started by Frank Miller with Batman in the mid-80s – of “Year One” stories. You take an established character and rewind back to the beginning of their career, digging into their early doubts and missteps. These stories have an aura of seriousness to them – they’re reaching for the definitive, and there’s a sense that everyone involved is taking a little more care than usual. “Lose Yourself” – and maybe the 8 Mile film it comes from – is Eminem: Year One, an origin story for 21st Century America’s newest super-creep.

There’s a convention in DC Comics – started by Frank Miller with Batman in the mid-80s – of “Year One” stories. You take an established character and rewind back to the beginning of their career, digging into their early doubts and missteps. These stories have an aura of seriousness to them – they’re reaching for the definitive, and there’s a sense that everyone involved is taking a little more care than usual. “Lose Yourself” – and maybe the 8 Mile film it comes from – is Eminem: Year One, an origin story for 21st Century America’s newest super-creep.

And true to the genre, he’s taking it seriously. Mostly in Popular we’ve seen Eminem playing the trickster, a dangerous goofball (first convincingly, then less so). When we’ve seen him get serious, on “Stan”, he’s dropped so far into character that what happens is more stage monologue than rap. But that won’t work for “Lose Yourself”, which has to be rap, straightforward rap, good rap, because the whole point of the song is bringing the moment to life when you step up, just you and your mouth, and let it flow. The centre of the track needs to be Eminem (as hero Rabbit) doing just that.

Around the edges, though, he can play with genre in more unusual ways. “Lose Yourself” is one of Eminem’s best-sellers not just because it’s good, but because as the hot track from a #1 film about rap it’s acting as an ambassador for the entire genre to a whole swathe of the cinema audience that doesn’t have an intimate knowledge of how rap works. Its production gives it a helping hand by nodding to quite different conventions – the brooding, rhythmic 80s rock of Flashdance or Survivor’s “Eye Of The Tiger”, music for films about gutsy battlers, fighting their way through a cruel world against the odds. Those resonances cue up that “Lose Yourself” is one of those stories.

It tells that story exceptionally well. The first verse of “Lose Yourself” is one of the best-known in Eminem’s career, a story of a scared kid stepping up to the mic and failing, which is entirely expected in Act 1 of a film but much less so in Act 1 of a hip-hop track. We don’t (or didn’t) generally expect rappers to inhabit humiliation and fear in the visceral way “There’s vomit on his sweater already – Mom’s spaghetti” does. The rhythm Eminem uses captures some of the nausea – he paces his stresses like a yo-yo winding out and jerking back (“snap BACK to reality OH there goes gravity OH there goes Rabbit he CHOKED”).

The second-verse Rabbit fails again, in a different way from the first, seduced and abandoned by success. In between the chorus is a barbed motivational speech – lose yourself, but you only get one shot at doing that. (Trust the force, Rabbit.) Again, this is hip-hop pushed into the familiar genre tramlines of the talented-kid movie, where the stakes are at their highest but you win success by a combination of trusting your innate, startling talent and respecting the craft you’ve adopted.

So let’s respect that craft and compare “Lose Yourself” to a couple of earlier examples of the hip-hop origin story track. The most celebrated is Notorious BIG’s “Juicy”, opulent where “Lose Yourself” is tense, presenting Biggie’s early life from a point of gentle wonder at all he’s managed to do. BIG is careful not just to handwave at the tradition he’s in but count off his forerunners by name – “Every Saturday Rap Attack, Mr Magic, Marley Marl”. He’s born from a collective. Meanwhile, Ghostface Killah and Mary J Blige’s “All That I Got Is You” stresses family strength in the midst of hellish poverty.

In both tracks the rise of the rapper is rooted in community or family: I love those songs, more than “Lose Yourself”, and I love them because they leaven themselves with nostalgia or sentimentality. “Lose Yourself” rejects those comforts for a world of battle. Its searing third verse is full of a desperation to tear away from circumstances – “I cannot grow old in Salem’s Lot!”. As a piece of rap craft, it’s a tour de force. Hear the way, for instance, Eminem incarnates his narrowing options by snapping his lines in two so their phrasing, amid his usual press of internal rhymes, comes out broken and awkward (“…get by with my nine to / Five and I can’t provide the right kind of / Life for…”) – it’s as ‘poetic’ a device as anything in “Stan”, and more exciting to hear.

The problem with Year One type stories in the comics is that, for all their craft, they’re something of a conservative pleasure – the delight in them is of pieces seen strangely, then fitting into familiar position. “Lose Yourself”, sticking closely to the cinematic coming-of-age formula, does much the same. Which means there’s not a lot of room for the more vulgar or mercurial parts of Eminem – it’s his most respectable track, the one where he’s not trying to shock or joke. And so for all its autobiographical aspects, it’s the one where he seems least himself.

Score: 8

[Logged in users can award their own score]

And this for me is where Eminem peaked in the first imperial phase of his career. It’s kind of funny how his pattern of singles followed a wildly similar trajectory to that of ‘The Marshall Mathers LP’: the comedic first single, the slightly angrier sounding follow up, followed by the harder hitting third single with a wide universal appeal despite it’s darker content. See, even rappers had carefully executed marketing plans.

I do feel ‘Lose Yourself’ is a stronger record than ‘Stan’ though, particularly as it also carries with it the added duty of being from a film soundtrack which could so easily have derailed it. It happily doesn’t sound so tied to the film and it’s storyline as to be parody ripe material (mind, I haven’t seen ‘8 Mile’ but I’m assuming it’s only loosely based on elements of his character’s rise to prominence in the film), and I would argue is tied with the non bunnied ‘Love The Way You Lie’ from his second imperial phase under a decade later as being his signature track. He is at the peak of his powers here in terms of flow, command and delivery.

As with ‘If You’re Not The One’ though, this was again absolutely massive despite being a one weeker and was still inside the top 10 as late as the beginning of March 2003, just as his next unbunnied single ‘Sing for the Moment’ – which I suspect is a Pointless answer – was released here. This is an 8, possibly 9 territory for me this one.

#2 watch – the seat very much being kept warm for two bunnies’ time as The Cheeky Girls, off the back of a much talked about audition on ‘Popstars: The Rivals’ debuted with ‘The Cheeky Song (Touch My Bum)’. A ‘How we made it’ piece on the making of this single with The Guardian (!) this month (https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/sep/03/cheeky-girls-how-we-made-cheeky-song-touch-my-bum) seems to suggest that this was being undersold by record shops at the expense of the two ‘official’ singles from the show to prevent it sabotaging the two official groups created by the show – although they technically did do just that to one of them. More discussion for that on the bunny after next, but it set them off on a year long run of top 10 hits that was only derailed by their record label, Telstar, going bust in 2004.

This was the perfect time for Eminem to do this, wasn’t it? A time when he still genuinely was unequivocally one of the best rappers on the planet, but when he wasn’t always showing it when not locked into Serious Mode, meant this was the best possible time for him to go into Serious Mode.

This is as calculated a number one as any we’ll see in this era – and that’s saying something – but those calculations are genuinely made in the name of being a good song, not just a profitable one. Yes, it’s shamelessly stealing influences from soundtracks to other films that had comparable character arcs, but those turn out to work very well with hip-hop beats, especially that stabbing riff (maybe as good a rock riff as we’ve seen on Popular since, erm, “Eye of the Tiger”) and the well-deployed orchestration.

Throw all those onto Eminem proving how good he could be – with his rhythmic play as well as his wordplay, and that third verse where the two collide – and you have a song that sounded like a potential instant classic the moment you heard it. Combine that with a narrative that allowed no room for the worst of Eminem to peek out (something not even Serious Mode was always a guarantee of, as “Stan” proved) and you have the Eminem song that could transcend Eminem.

And, for me, it does. It makes me feel more sad that he took the low road of misogyny and homophobia all too often elsewhere in his career, in fact. Why would someone capable of this too often fall to that? And for “that,” copy and paste… most of what he did after this, I fear. But that doesn’t take away from the magnificence of these few minutes. 9

#2 Yes, it’s baffling, isn’t it? “Lose Yourself” is brilliant, but also doesn’t feel like a one-off or dead end – the assumption I made at the time was that he would continue to produce similar tracks in the future.

If you were being cynical, you could argue that the tried and tested “The Little Engine Who Could” narrative runs through the lyrics here – pick yourself up, fall down again, then pick yourself up again until you become the achiever you were always born to be – but it’s so desperate, frantic and bitter in places that it ends up feeling more about someone kicking hard on the only fire exit available in case the worst happens. Not quite the American dream, that, more like the vision corrupted and turned utterly sour.

It’s also one of those rare records where everything seems to fall in exactly the right place. The intro is arresting, the verses build threateningly, the chorus punches, and the outro has an eerie tension that just makes you want to return and listen all over again. An easy 9 from me.

My understanding is that this has been SCIENTIFICALLY PROVEN to be the angriest Number 1:

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20180821-can-data-reveal-the-saddest-song-ever

I think I made a similar point to ThePenSmith on the Without You entry that the singles from The Marshall Mathers LP and The Eminem Show followed the same pattern although I saw Sing For The Moment as the counterpart for Stan with Lose Yourself as a one off soundtrack single.

I need to collect my thoughts on this and comment in more detail later. As has been mentioned Lose Yourself kept the Cheeky Girls from number one; while a massive release in its own right it was (as has been correctly said) a curtain opener for two bunnies along. Entering at number four this week was Robbie Williams’ Feel which is probably his finest four minutes on record. Curiously the Escapology album came out first which hobbled Feel’s chances of getting to number one. It would have been a sure fire chart topper most weeks but whether it would have outsold Eminem (and the Cheeky Girls) without an available parent album is something we can only speculate on.

I wrote that and then realised I could check the sales figures. Lose Yourself did a surprisingly low 91,000 while the last time Robbie released a lead single (Rock DJ) he shifted over twice that.

In my mind Feel coming out two weeks after the album was a risk he took as he saw how well Somethin’ Stupid did coming a month after Swing the year before. Only that was a Christmas race, and Feel wasn’t. It’s exactly the same thing as happened to Free as a Bird seven years earlier, which likewise came out in the first week of December a fortnight after the chart-topping album had made it available already.

I might or might not say more about Lose Yourself later on but yeah, great record. 8

The Cheeky Song was the only CD I ever shared with my sister, or rather that she shared with me as I liked it too much. What seems bizarre to think about now, given the uh, content of both songs is that for her 2003 birthday party the girls did the Cheeky Song and the boys did What I Go To School For.

#2 “Combine that with a narrative that allowed no room for the worst of Eminem to peek out”

The scene in 8 Mile where Eminem defends his gay colleague from homophobic disses in an impromptu rap battle seemed a bit rich. Like the autobiopic Mr Burns makes for the Springfield film festival.

That aside, good film and great song. I was saying Boo-urns.

I think it’s Eminem’s most compelling piece of music. Philosophically, its individualism and reckless urgency isn’t a step up from his petulant joshing brattiness, and the brattiness was more fun. But jokers aren’t taken seriously as great musicians — They Might Be Giants and Oingo Boingo never show up on polls of all-time great albums, for example, and even Weird Al’s original-music compositions are never credited with the brilliance that I think “Virus Alert” or “Dare to Be Stupid” or “Hardware Store” clearly show. This was Eminem trying to prove his worth in culturally respected currency, and he succeeded.

I haven’t been able to register an account, so I suspect my comment won’t show up if I attach a URL. But I recommend tracking down “Eminemium (Choose Yourself)”, by A Cappella Science, on YouTube. Replacing the musical backing with staccato close-harmony singing, Tim Blais raps with new lyrics about nuclear weapons and the cold war, for example

“Neutrons escaping from a source radiating

Merge and start atoms shaking; they begin

To unglue toward a decreased order

Entropic force distorts em

And supercharged with loads of protons they can only go farther

Cold war grows hotter–exothermal–Colorado to Joe Stalin

Coast to coast holes; silos but there’s no farmer

Toe-to-toe drama

NATO and Warszawa in co-assured trauma

The globe groans everyone knows there’s no calming

So show your foes and implode your core column

Quid pro quo Castle Bravo for Tsar Bomba”…

Building up to a plea for

“To a future in a safer spot, an irrigated plot

Homicide a way forgot

Success is a lack of military options

Failure’s not

Become a lover of a great and cosmic goal

We cannot condone these terror plots

So here we go it’s our shot

Feel frail or not

This is the only world and humanity that we got”.

The music is a triumph; the construction new, the purpose new, and every bit of the momentum and physical power carried over. Eminem and his producer made the structure. I respect that deeply. I’ll rate the original a 9 (and Tim Blais’s version a 10).

Some of the kids I taught had praised Eminem for a while but I struggled to connect to either his humorous or more downbeat material which is a reflection of my age as much as anything – at their age i’d been a fan of Alice Cooper. This was easier to like as I always associate the guitar riff with Led Zeppelin for some reason – something like Kashmir – so that initially hooked me in to this single. After that the increasing flow of words and riveting internal rhymes made this hard to resist.

Up to this point in his career Eminem had been making a big play of his authenticity and that he belonged in the same bracket as Dr Dre and Snoop Dogg – his MTV friendly looks were incidental to that.

8 Mile seemed to go against that, being an attempt to take the Eminem brand into films which is surely something his peers couldn’t do. I never got around to seeing the film (it was on the `to do` list at the time) but I understand that despite the potential for disaster it was a critical and commercial success with Eminem’s own performance praised – at one point he was talked of as an Oscar winner. It’s worth noting that for whatever reason he never attempted to repeat the trick and his subsequent film career consists of occasional cameos.

8 Mile is just one of several anomalies in Eminem’s career, not least that his violent past (and present – it was only the year before that an incident had seen him in a dock in handcuffs) never came back to haunt him. He was also able to reinvent himself more easily when trends in hip hop moved on.

There was, of course, a reason why Eminem was able to do this and I’ve been very hesitant so far to say what it was (his race). He may have resented the doors it opened for him but he also knew there was little point in ignoring them.

Re11: ‘being an attempt to take the Eminem brand into films which is surely something his peers couldn’t do’…

…I’m interested in exactly what you mean by that. Hip-hop and movies have had a close relationship since the early 1980s, with a lot of the early films being lower-budget variants on similar kinds of quasi-semi-autobiographical tales (graffiti tale Wild Style, Def Jam fictionalised origin story Krush Groove).

Meanwhile, by 2002, Snoop Dogg (since you mention him) had been a bunch of movies, many of them admittedly lower-budget, probably straight to DVD affairs, plus brief appearances in mainstream films like Training Day. The commercial high point of his film career would come a couple of years later in Starsky & Hutch. In the early 2000s Snoop’s fellow West Coast stalwarts Ice Cube and Ice-T were both a fair way into the process by which acting became their primary source of work – Cube had mixed the success of his self-scripted Friday comedies with roles in films as varied as Anaconda (Metascore 37/100) and Three Kings (Metascore 82). In 1999’s Three Kings, he is one of the trio of main players, and so gets his name at the same size on the posters as George Clooney and – a very different kind of sometime MC – Mark Wahlberg.

It’s true that for a film of its type – the Purple Rain genre? – 8 Mile had a relatively big budget ($40m v Purple Rain’s $7m 18 years earlier) – with a big-name director and a couple of established co-stars. Its success led to the same kind of budget and an award-season-friendly director being used for 50 Cent’s Get Rich Or Die Tryin’, to somewhat less profitable results.

In summary: did Eminem’s level of fame – and whatever complex relationship that might have to his whiteness – contribute to the scale of his introduction to the movie industry? Yes. Did it allow him access to a movie industry that was a no-go area for his black peers? Absolutely not.

Re12 You’re quite correct to say that other rappers had made inroads into film and a few had even successfully transitioned to film careers (and indeed the most successful may well have been Queen Latifah who gave an Oscar nominated performance in Chicago that year). So I wasn’t implying it was a no go area but previous rappers had to serve their apprenticeship.

My point was that Eminem was not only able to take his brand in to movies (8 Mile was effectively Eminem – The Movie) but that bosses were prepared to take a gamble on him as his lack of acting experience might have told badly. As I said it is noticeable that he never had a starring role again – he might have learnt from Prince whose post Purple Rain film career was something of a disaster.

Re13: Ah, I get what you’re saying.

What’s interesting, then, is that whoever forked out $40m to make Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ was ascribing 8 Miles’ success to it being a hip-hop movie, not a crossover-white-pop-star movie.

Re14: I might be wrong. However a glance at wikipedia suggests 8 Mile’s box office beat its budget by a whopping 200 million. It doesn’t say whether this was ahead of expectations but it might have suggested a market for a similar film even with a slightly less bankable lead. As it was Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ only just recouped its budget.

I have always respected the hell out of this song. This was clearly a musician at the peak of his powers. The percussive flow of his rap was lethal, and it synced perfectly with the synth-heavy production.

I have never, however, liked this song. Unlike the aforementioned Juicy, it leaves me absolutely cold. I had loved pretty much every Eminem release to this point, as outlined on the Without Me entry, but just couldn’t find a way into this one. It may be a technical masterpiece but I just find nothing tangible for me to grab onto.

Maybe it’s the big movie soundtrack element I don’t get on with – both Eye of the Tiger and Flashdance leave me similarly indifferent. I guess I struggle to separate these songs from the context of their films and imbue the with my own meaning. Probably I would have liked it a lot more if I didn’t know it was from a film. 5

A tale told in 3 parts.

———————–

The British and Irish Lions Rugby Union team journeyed down to South Africa in 1997 (in the eyes of the rugby public and most seasoned journalists) more in hope than expectation. The Springboks were the World Champions and the Lions were written off, largely as no hopers, going off to take the de rigeur stuffing that faced most Lions tours up to that point. Thanks to some inspired selection, masterful coaching and a team spirit etched in the liminal period of the game shortly after professionalism took hold, where the players were thankful for the opportunity to be paid for something that they were previously having to fit in around their work lives and grasped the opportunity with both hands, they won the series 2-1. Captured in a fly on the wall documentary that is a classic of its sporting type, Living With Lions shows this side being built, shaped and brought together under the auspices of the “tour song” – the one that all the players would sing together on a night out, and in the bowels of Kings Park, Durban, after an audacious smash and grab to win the 2nd Test and secure the series. Previous tour songs had been aired at what was then titled Sports Review Of The Year on the BBC – for instance, the 1971 tour song was Sloop John B and was sung on the TV by what is still the only squad from Britain and Ireland to win a series in New Zealand. In ’97, thankfully the squad was not asked to sing Wonderwall live for the nation.

———————–

2003 and another international rugby squad goes out to the Southern Hemisphere – this time more in expectation than hope. England, despite falling at the final hurdle in the 6 Nations on several occasions, had secured a Grand Slam in 2003 with a thumping win in Dublin, had beaten New Zealand in New Zealand and Australia in Australia in the lead in to the tournament. They were the favourites, the backbone of the forward pack had been on that 1997 tour as young men, and they too were united in song – this time, not to be sung by them, but listened to for inspiration. Lose Yourself was the back drop to this squad hanging on by the skin of its teeth – it turned out that that they had peaked 6 months early and played largely without inspiration in their pool, survived a big scare against Wales in the QF, bored France to death in the SF and then outlasted Australia in the final.

In this context, Lose Yourself demonstrates a few things. Clearly it was deemed to be inspirational – much was made in the squad of the opening spoken word segment (“if you only had one moment” etc) and the rhythmic backing track, echoing, as others have pointed out, Eye Of The Tiger and other jock jam classics works well blasting on a gym stereo whilst you try and fire out another few reps on whatever barbell you’re trying to press. It fits the moment and the occasion in this sense.

More generally though, it should be pointed out the shift that has taken hold in the population, as reflected by the England Rugby Union team. I appreciate that most here will look on rugby union with jaundiced eyes – the cliche of the toff, the beery nudity, the thuggishness, the exclusion of outsiders is probably uppermost in minds. It’s still fair to say that the finishing schools for young professionals in English rugby in particular are fee paying schools. But if you dig a little deeper, you’ll find that a lot of the time, these are boys on rugby scholarships, who don’t come from money, and are in their school grasping the opportunity being given to them, not just in rugby but in education more generally. In the amateur days, yes there were lawyers in the England team, and accountants and many other professionals. But a hard core of the team were farmers, policemen, Jerry Guscott from the 1997 Lions team started out working for British Gas. You’d be hard pushed to describe rugby as the sport for the toff if you went out and looked at the sport in Cornwall, South Wales or the Scottish Borders.

The game cuts across class in a way that is generally not appreciated (and why should it be? The sport could stand to do more to open itself up to a wider view of what it’s about), so it is my view that this team’s embrace of Lose Yourself, just 7 short years on from largely the same blokes singing Wonderwall, shows just what has happened to the lingua franca of Pop. It’s not rock music anymore, it’s hip hop – but it’s the middle ground, guitars still present, white man fronting it. A group representing more of the nation than might be thought moving away and into the new pop world that we will see more and more of as time goes by. There will be white boys with guitars getting to number 1 from here on out on Popular, but fewer and fewer of them, as the cross cutting acts that connect with the widest public begin to be more and more influenced by R&B and Hip-Hop – due to my perspective of this through the lens of the sports I watch, this song in particular, artfully put together, rapped with feeling and technique that even a lay person such as myself can spot and appreciate, is the one that really put the nail in the coffin of rock as the prime language of music, whatever the NME and the New Rock Revolution bands has to say about matters. It’s coruscatingly brilliant, undeniable, and – frankly – a welcome break from all the sub-South Park/slasher movie bollocks Eminem was going on about elsewhere in his catalogue.

———————–

It’s 2013 and the Lions are on tour again. This time, they’re in Australia and the night before gave the Wallabies a thorough smashing in the final Test of the series, thus winning 2-1. The end of a long season and euphoria in a job well done means that the side has been out for a few beers. The Guardian journalist Andy Bull enters a lift in the hotel he happens to be sharing with the Lions. Three children are in there with their dad as the lift descends, stopping to pick up Jonathan Davies – Welsh centre and stand out performer in the final Test, Leigh Halfpenny – Lions fullback and man of the series, the deadliest goal kicker in world rugby at that time and defensive rock, and Mike Phillips – perhaps the definitive “good tourist” who seemed to always save his best performances for long trips away from home at World Cups or Lions tours. The father, a man of average build, breaks the silence. “Jeez, you blokes are so big you’re making me feel a little insecure.” Halfpenny, it has to be said, was not wholly sober. Suddenly he started to sing. “You’re insecure, don’t know what for. You’re turning heads when you walk through the door!” By now he was clapping his hands and doing a little jig. By the time he got to the chorus Phillips, Davies, and all the kids had joined in: “Baby you light up my world like nobody else!”

By 2013, the nation’s rugby players are singing One Direction and the wheel continues to turn.

Eminem is a real blind spot for me I’m afraid. This just feels overlong and tedious to me. 3/10.

To me it illustrates the gulf between transmission and reception, and how a song can mutate into something the creator didn’t intend.

The verses tell a harrowing story of self-doubt and loathing. It’s not rags-to-riches like “Juicy” – the aspirational parts sound like a madman talking to himself, and the imagery dwells on motifs of fantasy and deception (“Make me king, as we move toward a New World Order”…”Best believe somebody’s payin’ the Pied Piper”). We see none of Biggie’s awe of rap as an art form. Rabbit’s as cynical as he is desperate: rap’s just his lottery ticket out of a shitty life, and probably a rigged game anyway.

I’ve never seen Eight Mile but the song implies success wasn’t worth it in the end. Note the verse about food stamps and diapers that comes AFTER he’s touring coast to coast, living the dream. Lots of mid-level musicians and athletes end up like that, they break through, achieve some success…and by 40 they’re broke and finished, having sold their soul for a cardboard trophy.

But all of this negativity is swept aside by the huge adrenaline rush of the chorus. It’s so overwhelming that “Lose Yourself” becomes a hymn to perseverance, despite the song’s fundamental negativity.

It’s almost as ironic as “Born in the USA” becoming a patriotic anthem. “Lose Yourself” is like a car jack used to hold up a broken bedframe – it does the job well, but it’s not quite the job Eminem meant for it.

>BIG is careful not just to handwave at the tradition he’s in but count off his forerunners by name – “Every Saturday Rap Attack, Mr Magic, Marley Marl”. He’s born from a collective.”

And who could forget that seminal hip-hop classic, “The Rappin’ Duke”.

My second single purchase from Eminem. The first was ‘My Name Is’, though I did own ‘The Eminem Show’ album also.

This one more so than that debut was unavoidabl and was perhaps the confluence and peak of Eminem?

The movie, the music, the press attention, the controversy.

A thumping, energetic track that was motivating. Not something his single discography was particularily known for at that point, impressive though it was.

This was a moment in time, perfectly captured.