Branding, unsurprisingly, started with cows. When it moved from livestock to consumer goods, it expanded from a mark of ownership to a mark of consistency, but also of quality. As Andy Warhol put it in 1965, “All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.” The same went for Barbie.

Branding, unsurprisingly, started with cows. When it moved from livestock to consumer goods, it expanded from a mark of ownership to a mark of consistency, but also of quality. As Andy Warhol put it in 1965, “All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.” The same went for Barbie.

What this meant was brand owners could begin to decouple consistency and quality. If all the Cokes are good, they need not actually be the same. You can have Diet Coke, Cherry Coke, Vanilla Coke. You can have coke bottled in Bialystok and Bilbao. You can have squirts of Coke syrup mixed with nozzled soda water, and by the power of the brand, all of it is Coke. The material existence of the product and the symbolic existence of the brand become more separated than ever but also more mutually dependent. Marketing, advertising, research (and a chunk of Warhol’s art) is very often about understanding and exploiting the relationship between them. The product Barbie creates the brand Barbie, but the brand Barbie is what then makes the existence of Ken possible.

By the late-90s – when I sold out and started working in the ‘communications industry’ – excitement in the symbolic side of branding had reached a new level. Much of the talk was around the intangible assets a brand represented on a balance sheet – its “equity”. But the new models of branding held that those assets sprang from a brand’s existence as a symbol for something wider than just a product range – what it represented in people’s mind beyond the product. Escape. Joy. Security. Rebellion. This was its brand image, or brand personality. Coca-Cola, for instance, meant happiness. Volkswagen meant safety. As for Barbie, Barbie meant fun, imagination and aspiration – three qualities the brand knotted firmly together. “With Barbie”, gushes the Superbrands site, “A little girl can be whatever she wants to be!”. A paragraph or two before they write “Barbie is always successful… always fun.”

Marketers and businesses loved this new emphasis on the symbolic aspect of branding. For a start, if a brand could plausibly claim to be different because of its ‘personality’, it could make savings at the sharp end, in production and quality control. But more – aligning a brand with happiness or fun ennobled it, and let marketers see themselves as something more creative than simple businessmen. Like artists, brand owners had their hands deep in the clay of the human psyche, manipulating powerful, ancient ideas. Research into brands became ever more focused on brand image – whether or not people could detect their symbolic identities.

This emphasis on brand image had two huge potential flaws. First, business people were not especially good at the manipulation of symbols. They tended to approach brand in the same way they had approached production – something to be set, scaled up and controlled. They wanted their brands not just to be symbols, but fixed symbols, which left them running to catch up with more playful or imaginative uses of their brand. “Subverting” a brand is one of the oldest tricks in the DIY artist’s book, but it works partly because brands are – or were – so uptight about their symbolic potential.

The other flaw is that brand image glossed over the other side of branding – the everyday reality of the product. And not just the often awful conditions in which it’s made. Marketing books are full of stories of managers spending time with the people who actually bought their stuff and being astonished at what they actually did with it. The idea that the intended use of something and its actual uses are different is a no-brainer for any critic, just like the idea that fixed symbols are vulnerable to inversion and playful manipulation – but marketers have rarely paid much attention to critics.

“Barbie Girl” works because it hits both of these brand flaws at once. It starts from part of the everyday reality of dolls which is absolutely familiar to most adolescents but which Mattel can’t directly admit: one of the things bored kids of a certain age do with toys is make them have sex. And then it exploits the Barbie brand’s attempt at being a fixed symbol for fun by making Barbie’s chirpy sexy funtimes be an exploitative relationship with a leering brute.

For me, both of these succeed because of the other – it means “Barbie Girl” doesn’t settle down into commentary or crassness. Crassness on its own gets you “Cotton Eyed Joe”. Commentary on its own is more worthy, but ends up fighting fun with not-fun, often to their mutual bafflement. Aqua, very obviously, are flirting with crassness a lot more than anything else, but they’re also happily complicating their hooks-first annoyance value at the same time as they push it unashamedly hard.

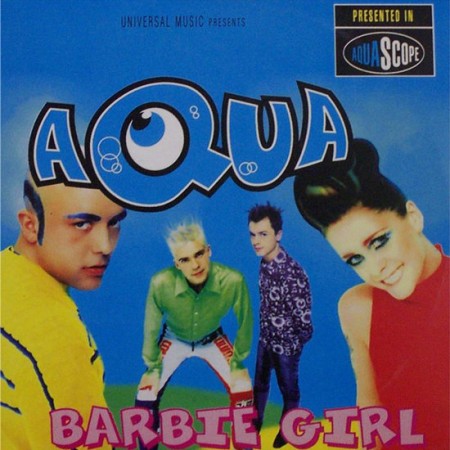

Their best – meaning funniest – asset in all this is René Dif as “Ken”, playing the Einar to Lene Nystrom’s Bjork. At the time some critics took “Barbie Girl” entirely at face value and condemned its Neanderthal attitudes and/or gross materialism – criticisms that really shouldn’t survive their first brush with Dif’s saucer-eyed, wolfish voice, which is absolutely committed but an easy tip off that whatever else this record is, it’s not seriously endorsing much of anything. Most of the rest of the anti-Aqua focused on the record’s hammering catchiness – “Barbie Girl” infuriated enough people to be voted the worst record of the 90s in Rolling Stone, only three years ago. People can’t choose what annoys them, of course, so all I can say is that this song doesn’t bother me. Aqua – like most Europop – are remorseless in their dedication to earworming you, and accept your later loathing as collateral damage. After four weeks I was as pleased as anyone for Barbie to bugger off back to her dream home, but I’m happy to hear the record now.

The third big criticism of “Barbie Girl” is that it sexualised Barbie. There’s no way of refuting this – it’s much of the point of the record, and even if the lyrics had no undressing or hanky panky, the entire duet dynamic relies on smutty oversinging, So why not go all in? Another way of hearing “Barbie Girl” is as a consensual kink scene – playing dolls as playing roles. The (glorious) video even backs this up to an extent: Barbie World may well be Barbie’s world, but Lene and René are certainly making no attempt to cosplay Barbie and Ken (“Why is Ken bald?” cry several of the 110 million YouTube viewers). They’re tourists here, having a splashy delight of a time, acting like naughty toys. In the final scenes someone dressed very like an actual Ken shows up, and looks – like Mattel – entirely horrified.

A footnote: In my outline of branding I’ve stuck to the past tense because attitudes have shifted a little recently – the Internet has forced brand image to become more flexible and has seen a huge surge of interest in ‘user experience’ which connects brands and products more intimately. This will end up being important to Popular – honest! – as you can also see a difference in how pop acts are conceived and marketed. Meanwhile, Aqua’s ambiguity is something a savvier company can and will catch up with – after years of embarrassingly trying to sue the band, Mattel inevitably ended up in 2009 just adapting “Barbie Girl” for an ad campaign.

Score: 6

[Logged in users can award their own score]

This song marks the only occasion on which my music writing for the student newspaper ever received comment. I did a ‘classic album’ review of Aquarium, and as an adjunct to that wrote a rather long* thinkpiece on the feminist implications of “Barbie Girl” (readable here) – this was, of course, too long/borin^H^H^H^H^Havant-garde for the paper, but they supplied my email address at the end of the article for anyone who wanted to read it to contact me via.

A week later, I received an email – from the editor of the newspaper, formally apologising to me for publishing my email address, since it transpires this was against the newspaper’s code of practice.

Anyway, this is an occasion where the bunnies are so much better that I think of “Barbie Girl” as bland by comparison and somewhat resent its being so much more famous. Good drumming tho’. 5?

*’rather long’ to be taken in comparison with the paper’s typical Christgau-sized reviews – it’s probably shorter than most of Punctum’s opening sentences

For me this song is at the absolute pinnacle of its genre (i.e. gleefully novelty Euro-pop).

I love Aqua. A little of their chipmunky pop-art goes a long way, but they were always a lot smarter than their critics gave them credit for.

I also adore a forthcoming Bunny where they briefly wrong-footed everyone who wrote them off as a one-trick pony. But we’ll get to that.

Woah, I had completely forgotten about this. Such a magnificent, clever, catchy, cheeky, hooky record, it is pure joy. ‘Absolute pinnacle of its genre’ is right. (10)

Fabulous write-up around what is really a pretty fabulous *product* (the video being a near-essential accompaniment to the song). Lene’s strained little-girl-lost voice – clearly put on as part of the act – would be grating at greater length, but, along with René’s vocal leering, it’s all part of the show, and key to the chararacterisation.

Good, unexpectedly intelligent, pop that reveals itself as a delight once the initial, quite possibly intended, sense of irritation has worn away. 8.

(on branding, and as a not entirely unrelated aside: to my knowledge only one Scando-pop act has had their name, or a slight variant thereof, adopted by a mobile phone operator: Ace&Base, serving Ukraine a few years after the height of the melancholy Swedes’ fame. Can’t help thinking an Aqua-fon might have been a bit more playfully, engagingly, fun)

I don’t remember seeing the video before – but it’s a lot of fun. That and the song are like a poppier response to ‘In Every Dream Home a Heartache’.

Sample watch: The drums are from “Give it Up” by The Goodmen, and are therefore the same drums as on Fairground by Simply Red.

My brother played this on repeat while I was on the computer. When I hear it I still see Sim Tower.

As an indie music-loving teenager, obviously I hated this when it was out – and yes, would probably still hate it if it were on the radio all the time. Nowadays, when it’s more commonly encountered on late night music television or in karaoke booths, I faintly love it to the extent that I’d have given it a higher mark than 6.

Torn.

‘Nuff said.

2.

6: I’m absolutely gobsmacked by this! I mean it’s obvious now that I know, but so many times I heard this record and never even noticed the beat, let alone placed it.

Time has been kind to “Barbie Girl”. I tend to smile when I hear it. And I too, believe it has a deeper feminist message, like “The Land Of Make Believe” was a critique on Thatcherism, BG held up a mirror to what the Patriarchy expected young girls “should” aspire to. Yes, BG is much more feminist than any declaration of Girl Power. Not that BG made me think about the Patriarchy in 1997. When I first heard this on the radio, I thought it was Whigfield with a comeback single. Aqua? Who is this Aqua? MTV provided the answer with the bright cartoon-coloured video. It definitely put a different spin on the song, watching Rene’s leery “come on Barbie/let’s go party” interjections. But a pop song as seemingly simple as this can be fashioned to fit anyone’s view, for good or ill. Either skip along the surface and see it as nothing more than a song about a doll, or delve deeper and think about how a little girl’s interactions with her doll is how they make sense of the world they exist in. And how a male-dominated society skews their dreams and ambitions. How girls are taught to apologise for being girls, how the burden of being a girl in a man’s world, means everything from hair to shoes is so much hassle.

What do boys have to do? Mostly keep their pits and privates clean and wander through life without having to worry about what others think of them, or if anyone is following them or judging them or if today’s the day they get raped.

My daughter played with Barbie and Cindy, her British competitor. She was too old for those Hip Hop usurpers, Bratz. The Cindy dolls used to belong to her mum. The Barbies were birthday and Christmas presents, presented in garish Pepto-Bismol pink boxes with accessories and outfits and shoes. The outfits for both were interchangeable, although Cindy’s paisley leisure-suits and maxi-dresses clashed with Barbie’s on-point ’90s fashions. It didn’t matter. What difference is there between Twiggy and Cher Horowitz to a 10 year-old girl? They all ended up with back-combed hair poking out of pink or yellow hair-bands, lined up in a row as my daughter re-enacted school more often than not. Ken never got a look in. Ken never featured in her world. After what seemed like a few short months, they all ended up back in the box in the attic as her attentions turned to Beanie Babies. Such is the fate of all Barbies, one supposes, packed in a box in the attic until the next generation come along to play with them again. Barbie doesn’t rot. Barbie will “outlive” us all. One hopes the attitudes that Barbie helps to reinforce, wont.

Since I’ve been following this site regularly, I’ve tried to guess what Tom’s rating is going to be based on his past preferences. Sometimes I do better than other times (The Verve’s low rating surprised me; CITW’s did not), but this record may have been the hardest to guess yet. Brilliant piece of catchy satire, or cheesy piece of annoying crap? I was pretty sure 10 wasn’t happening, but honestly any score from 1 to 9 would not have shocked me.

So I’m happy to see it get a decent score. I myself am wavering between 7 and 8 – it seems the very definition of “earworm”. I wouldn’t want to hear it over and over again, but in small doses, it’s quite fun. And making fun of a well-known brand is just an added bonus.

Back in 97, this was one of those occasional hits that was unique enough to inspire its own newspaper articles. In fact, I think this may have been how I was introduced to it, reading about it before I actually heard it on the radio. It peaked at #7 on the Hot 100, which understated its US impact as I think its chart life was affected by a limited single release which may have in turn been caused by Mattel’s legal pressure at the time. I remember the video was particularly popular – kind of a Youtube-type meme before there was a Youtube. It spent multiple weeks atop the request chart of video channel The Box, which was otherwise dominated by hardcore rap videos that MTV wouldn’t touch.

This song appeared to be a classic one-hit wonder at the time, but as we know, we’ll be encountering Aqua twice more here. Of course, this wouldn’t be the last time a successful career would be launched with what many would consider a novelty hit – a far more spectacular example will occur 11 years later….

This was a fun track. The female singer sounded like she was channeling early Madonna (though with, of course, less impressive musical results).

#12 That’s quite unfair to Alexandra Burke, I can’t help thinking…

I’ve never really associated it with Barbie as in Mattel’s Barbie. Maybe because she doesn’t have blonde hair. It hardly matters as I think this is chronic gunk, facing in the opposite direction, ho hum.

Kind of surprised nobody has drawn parallels between the Girl Power marketing of the last entry and this. Barbie the brand found itself unwillingly repositioned in the 90s, and not in a flattering way – Mattel may have been baffled that their creation had stopped being progressive (she can be a surgeon! She can be black! Well, one of her friends is, but it’s the same basic doll extruded in dark brown plastic, does it matter if we put a different name on the box?)

But this record plays to the new cultural shorthand image of Barbie, seemingly obvious though actually relatively recent (in terms of the doll’s lifespan): the perception of Barbie as an airheaded bimbo, a vapid woman with a defined and defining role in a patriarchy, not only an unsuitable role model but actually a potentially damaging influence, from body image to intellectual ambition to relationships.

One of my favourite things about the record is that it plays Barbie as a pathetic, tragic figure (I won’t say “sad” as it’s not actually made clear whether the narrator is meant to be happy with her lot). To take Tom’s imagery one step further, at what point does a doll being put through the motions of sex become an out and out sex doll?

By using Barbie as an implied pejorative – take a good look, girls, is this REALLY what you want to be? – I think it becomes a kind of cautionary tale which makes a great deal more of an effective Girl Power point than, say, prancing about in your pants, or a Union Jack dress. Had the Spice Girls dolls hit the market at this point?

Also, it’s maddening in its catchy pounding, which is great. 7 or 8 for me.

I was half dreading going near this one as I expected a hostile reception given the ‘worst song/Number 1 ever’ existence it has had to endure but I’m delighted to read the largely positive comments so far. Don’t know if this is the best comparison but it seems like the ‘Japanese Boy’ of the 90s.

When you consider what Tom has had to endure since Hanson I wouldn’t be annoyed with BG at all. Fair dues for Aqua to make a universal single – wish i’d thought of it.

The package is what sells it here. Fun name, Cracking video, Inspired title.You couldn’t ignore it really.Like CITW perfect for substituting your own words to it which was surely done everywhere but unlike CITW a very welcome listen.

A 7 for sure. Best get back to proper geezer music like Oasis/Blur now and pretend that I’m outraged by this!

heymanrememberthenineties? love how this is a mix of 90s ironic anti-corporatism (by this point hardening into an adbusters/baffler shell) and boom economy giddiness. for me in 97 it was part of a string of ridiculously shameless pop singles that i fell in love w/ that summer, each better than the last, ‘barbie girl’ being preceded by los umbrellos’ now forgotten ‘no tengo dinero’ and followed by the chumbawumba’s still recurrent ‘tubthumping’. it occurs to me now that all three play w/ that ‘children of marx and coca cola’ dynamic. i played the hell out of stereolab that summer as well.

listening to ‘barbie girl’ now what strikes me isn’t the obv lol 90s aspect of it but how surprisingly contemporary this thing could be, released today it would be obvious clickbait pop a la ‘gangnam style’ and ‘the fox’, the sort of corrupting force in the charts whose presence at #1 would be indicative of how things are wrong now, how the internet has changed everything. still, it’s no ‘tubthumping’. it’s no ‘gangnam style’ either. 6.

As someone who is not much a fan of Europop by any meas, “Barbie Girl” kind of terrifies me because it does something I don’t think should be done and it does it very, very well — probably better than anyone ever has. This absolutely deserved to be a number one hit, for better or worse.

I can’t separate this from all the feminist Barbie theory I read in the early 90’s. Her lack of a real response to the “c’mon Barbie let’s go party” also makes me think of the college consent codes and no-means-no culture. There’s no way I could have not seen this as a feminist record in 1997. 8 or 9 from me, it might be a 10 if I could stand Ken (Einar’s) voice.

Re Coca Cola: I knew someone who attended a presentation by a senior Coca-Cola executive in 1981 or so, and the exec said “Coke is only ever Coke, and there will never be a Diet Coke.”

My Dad, who had recently turned the age of thirty, picked me up from school one autumn afternoon. “I just heard the worst song ever!” he said in the car on the way home, eager to hear my reaction. “It goes ‘I’m a Barbie Girl in a Barbie world’?!” I laughed, thinking he was joking. Soon enough I heard for real what he was talking about.

This outpeaked ‘Wannabe’ as the song that I decided I hated more than anything else in the world. It was about GIRLS and only girls liked it, stupid icky girls and I bet whoever likes this likes the Spice Girls as well. Any irony or parody went completely over my head – indeed I thought the song was a complete celebration/idolisation of Barbie and would not have been surprised had I learned it was produced by Mattel themselves. So I made up my own version to amuse in the school playground. Sadly today I only remember half of it, starting with “You can eat my hair, and throw me anywhere, imagination, nothing’s your creation”. Then Ken’s bit turned into “Barbie I don’t want to go party”. My fellow Year 4s judged it hilarious, and for the first time – if briefly – I could actually consider myself cool, even with the older Year 6s.

Can’t really bring myself to give it more than a 6 today as I never had that real liking of the song over a million others did, but agreed production-wise it *is* the late 1990s and a very well put together song. What I didn’t know was that they’d get better, to the point where by 1998 I could happily call myself a fan of theirs!

Tom, I find your ‘two huge potential flaws’ paragraphs difficult to follow: is the difference between the two flaws just the difference between two sorts of audience? Semiotic sophisticates/subversives will turn your product on its head for their own ends, ….and so will, to a smaller but more potent degree, kids’ own uses of the product. On this reading, Aqua are both arch sophisticates and kids who grew up ripping their dolls’ arms off, etc.. Is that what you’re saying? But if so how does that distinguish them from everyone else who’s mutilated a few dolls in the name of high art/protest, etc, e.g., Cindy Sherman?

I tend to think that Aqua differ from Sherman, et al. in that they have at least some affection for the damn doll and the idealized happy life it represents (not so different, after all, from the glamorous world of pop videos or the fashions of Clueless), and ingeniously their song tries to not only get inside Barbie’s head but also make sense of a whole strand of persistently ludicrous pop music, i.e., as what Barbie and Ken listen to.

I didn’t get this myself immediately at the time, but I was brought up short when my ultra-feminist g/friend dug the hell out of the tune. Part of her response was just that, ha, she loved to set aside the weight of the world and bop around to Hi-NRG pop, but the other side was the track’s true ingenuity which she had to explain to me. Just as The Matrix‘s master-stroke (and the thing it had over all of the other’90s ‘virtual reality’ films (13th Floor, Existenz, etc.) was that it provided a kind of retrospective explanation for martial arts movies (‘they can do all their wild moves because they’re in a mind-constituted Matrix’). Similarly, Aqua’s master-stroke is retrospectively explaining everything from The Archies to SAW to 2 Unlimited to Whigfield (and predicting the appeal of Nsync, Krazy Bunny, What does the Bunny say?, etc.).

Note that there was plenty of griping but amusing thought in the early ’90s to the effect that ‘that bitch Barbie *is* everywhere, she *can* do anything’. Here’s Kathleen Hanna in Melody Maker in 1994:

“You know how there’s a Rap Barbie doll? We in Bikini Kill have got this feeling that they’re gonna start manufacturing a Riot Barbie. And she’ll come packaged with a little beat-up guitar, some miniature spray paints that don’t work and a miniature list of dumb revolutionary slogans like ‘Riot Coke just for the taste of it’.”

One person’s subversion is another person’s brand extension and occupation of every niche I suppose. Anyhow, BG both depicts Barbie’s World and raises the question of the extent to which that’s the real world. That’s conceptually superb in the way that ‘Setting Sun’ was, or ‘Relax’ and ‘Two Tribes’ were. The music’s not quite at the level of Aqua’s follow-up tracks, but this is their conceptual high-point and in my books it’s an easy:

8

The thing I loved about Aqua was their ability to present adult life in all its complexity as a fun game for everyone to play. The videos are an essential part of this, and Barbie Girl in particular is a complete success – a parody, a cultural critique and social commentary all rolled into one, but never feeling preachy or pessimistic. Other examples of this sort of thing tend to have too much of a knowing wink about them, but Aqua are happy to invite everyone, whether they ‘get it’ or not.

A 9 for me.

Swanstep @22 – The Fox isn’t a bunny, in fact it only got to number 17 in the UK. Surprisingly enough for such a big novelty hit it only got to #1 in Norway.

@weej, 23. Thanks for that clarification. I don’t pay close attention to the charts these days, but I tend to just assume that if I hear about it (esp. through my nieces and nephews) then it must have topped the charts (and charts seem so close to uniform across the world these days). In this case the enthusiasm of my young relatives for the track – in their world it was huge! – misled me.

On branding: I appreciated Tom’s opening to this entry. I have a (possibly inside baseball) question on this though. I work in market research for a company that makes stuff for kids and, through that work, have struggled to work out whether kids (below a certain age at least) have any real concept of brands, at least that they can articulate. When you ask them about their favourite toy/TV channel/game/website and why it’s their favourite, they don’t tend to say things that you tend to think of as brandable (a good example is TV channels, where they tend to say something is a favourite because it’s got x, y and z show and I like them – not that the channel itself is funny, interesting, dramatic, etc). In some respects, this is quite refreshing – kids won’t just swallow any old rubbish that you’re trying to tell them about some product or other. This has lead us down the route of advertising features of the products rather than anything more brand led or sophisticated, that kids just don’t appear to get. On the other hand, there are branding elements that clearly work for kids, even if they can’t articulate it (monkeys advertising Coco Pops for instance).

So, when it comes to down to it, who is the branding around Barbie for? Is it for the kids – and it’s having some subconscious effect, or is it for the parents (who will probably be the gatekeeper for whether Barbie is put in their child’s hands)? Or both in some measure?

On the song: this is alright, I reckon. Satire wrapped in europop that I don’t really want to listen to more than a couple of times. Tied into the above though, I’m not sure that the actual point of it would have been got by children – not that this necessarily matters, though I guess it might – so I look at it as a weirdly adult message wrapped in something that might appeal to children, like a good Pixar movie. I would have been up for Torn getting a week at #1 out of Aqua’s 4 though. Would have been nice to have both.

#25 Young kids react to branding on a fairly visceral logo-association level (the cattle/consistency level) – every now and then you’ll get a horror-story poll going round about 3 year olds recognising McDonalds but not their own surname (or something). The thing about shows and channels is interesting – kids don’t particularly care about umbrella brands like a channel or a supermarket, and they don’t really get branding in that sense, but they do get congruence (which underpins a lot of branding). I used to play a game with my kids called “Daddy Got It Wrong” where I would get details of a show wrong by inserting some character from a different show eg “My favourite episode of Chuggington is where Spud switches the signals so all the Chuggers get confused”, which was the cue for the 3-year old in question to bellow “DADDY GOT IT WRONG” and explain that Spud was in a different programme.

But I think that changes fairly early. CBBC/Cbeebies (as we’ll be talking about very soon!) is a good example, because the branding is grounded in something the kids do think about once they start school – is this babyish/something I’ve grown out of? I think a more adult sense of branding starts creeping in too – my 7 year old just had to do the “what do you want to do when you grow up?” talk at school, and his answers (footballer and videogame designer) included the detail that he would be a designer for “Nintendo or Activision”.

Said 7 year old also found “Barbie Girl” hilarious and horrifying, unfortunately because “it’s for girls” rather than anything else. (My 4 year old loved it and ran around going “Barbie let’s go party!” for ages.) Which is the really pernicious element of branding and kids – the stuff that works tends to be the stuff that goes with the grain of gender-specificity in the culture, which in turn creates even more of it.

“Torn” is definitely one of those songs that ‘should’ have been a number one but to be honest I’ve never liked it that much and I’m no sadder that I don’t get to write about eg Texas.

I remember this as being simultaneously aggressively inane and infuriatingly catchy, both to a high degree; however, at seventeen years’ remove it comes across more as harmless, albeit mildly enjoyable, nonsense. I can’t help wondering what was wrong with her voice, though. SIX.

#22 The two flaws are related, certainly – they both center on the way branding leads to a kind of corporate self-absorbtion. The first though is a sin of commission – companies trying to fix the abstract/symbolic meaning of their brand which leaves them (more) vulnerable to other people’s play with it – or just to the drift in meaning that comes from them being unable to control who buys it. (There’s another related issue – the belief in “target demographics” – but that’s actually more relevant to the next two entries…)

The second flaw is a sin of omission – marketers caring so much about their brand that they lose touch with how it ‘works’ in the real world. This has a much easier solution – it’s not actually that difficult to do “consumer ethnography” or UX. I think you’re quite right about the difference: the enthusiasm for the product – which is definitely part of Aqua’s deal – is crucial here. Aqua are making dolls have sex as a version of ‘playing with dolls’, it’s still playful and silly and imaginative i.e. still well within the use-cases of a toy.

Cumbrian @25: “Parents … will probably be the gatekeeper for whether Barbie is put in their child’s hands” underestimates the devastating power of the wrapped Christmas/birthday present from extended family.

I had somehow missed this song’s growing reputation as the Worst Ever, although remembering its late-1990s reception it shouldn’t surprise me. I might have been tempted to think that myself, given my musical proclivities, if not for the fact that my wife loved it, and Aquarium was rarely off our CD player at one point. Aquarium has a fair claim to being the Europop album of the 1990s (but as the Bunny shall eventually reveal, only my second-favourite Europop album of the decade): looking at its Wikipedia entry I see that seven of its 11 tracks were singles, which isn’t that surprising – the surprise is that some of the remaining tracks didn’t form an 8th or 9th. I’ve just relistened to it, and only one track (“Be a Man”) strikes me as a weak single prospect, which is pretty incredible.

Thinking on it now, I realise that I’ve always grouped Aqua in my mind with No Doubt, with “Just a Girl” and “Barbie Girl” as the mission-statement hits, and parallels in their subsequent singles as well. The cover of Tragic Kingdom also has echoes of what Aqua did with theirs, all bright and cartoony. The strong Aquarium brand replaced a couple of more literal single covers for their first two Danish singles (photos of the band visiting an aquarium), and feels like a master-stroke of marketing. It’s hard, too, to imagine them doing as well with their original band-name of Joyspeed, although it does suit their music. (If you’re curious to hear what proto-Aqua sounds like, YouTube provides. Of course it would be a nursery rhyme. Not only that, but my daughter’s favourite nursery rhyme. I’ll have to try the rap section on her.)

I don’t remember ever doubting the subversive stance of “Barbie Girl”, or thinking that it was a simple celebration of the toy. Some of that must be down to my wife, whose ingrained feminism wouldn’t have let her enjoy any sort of uncritical celebration of Barbie, not even ironically. But the clues aren’t exactly hidden. “Life in plastic, it’s fantastic” was obviously not to be taken at face-value in the late 1990s, when “plastic” had long been a byword for fakery and cheapness, not to mention its reputation as an environmental menace and symbol of overconsumption. (I read this fascinating history of it around that time, which gave me a better appreciation of the much-maligned stuff, but there was no doubting its popular reputation.)

I’m amazed to see “Barbie Girl” described (on the blurb at the top of its Deezer page) as “one of those inexplicable pop culture phenomena”: what’s inexplicable about a song crammed with hooks which can be enjoyed on multiple levels becoming a hit? I wouldn’t dismiss those who hate “Barbie Girl” – if you don’t like Europop you’re gonna hate this, and even if you do this could irritate in other ways – but there’s no way I can give one of the key songs of the ’90s anything less than 8.

(The critic I was referring to in the piece who took BG at face value was J1m D3r0G4t1s who is reliably tin-eared about everything)

#26: This is interesting (to me at least). I think a functional problem for quite a bit of the research that is done in my organisation is that none of us have kids – there are few of us of the age that are even considering it to be honest – and I think it inarguable that, although the sample size is small, constant immersion in what is going on is more instructive than getting 2 hours worth of time with a wide variety of kids on a semi regular basis.

There’s definitely a sense that kids will quickly discard things when they find them babyish and we see that a lot. That said, the number of 7 year olds still hanging in with relatively young products that I have seen has given me a bit of pause. Ultimately, I suspect it is about stages not ages, and have seen evidence that kids quickly learn about the types of things that they won’t talk about with other kids (in case they get teased) but will continue to enjoy on their own. Children obviously mature at different rates, so it seems sensible to view their world through this prism – but it is very difficult when business is generally done on the ages that children are at (for good reason in the main, as they are still likely the easiest way to draw some generalities that can be aimed at – NB: I wrote and hit comment on this before seeing your comment at 29 – I too have a bit of a distrust of target demographics but have to use them, otherwise I’m not going to get anywhere in terms of delivering required work in company).

I also found your comment on umbrella brands interesting. I doubt this is supported in the theory on branding but aren’t all brands umbrellas in some sense? What makes Coke Coke is a collection of traits and I imagine that if Coke did something that was incongruent, kids would be able to pick it out.

Another thing I have been playing around is that , I think, some of the things kids take out of brands are things like “my friend has a Barbie, so I like it because I like her/it means I can play Barbie with her” etc, which kind of brings in some of the things you’re talking about re: gender specificity. There’s been a general move at my company to try and develop things with regard to play patterns rather than genders (in some respects) but whatever happens, we still find that the traditional boys stuff sells to boys and the reverse – even though that’s not the explicit intention. There’s a lot of influencing stuff in the ether, in general, around how kids grow up and what they get into. In my experience, a lot of it is reflections of parental experience too, which I think is a reinforcing factor (we see a lot of “I played with xxx, so I trust it and will put xxx in my child’s hands”/”I watched xxx, so I am happy for my child to watch xxx”). In some respects, this is why I am interested in who the branding of Barbie is for? I genuinely think that the primary audience for Barbie branding is parents but I am willing to be persuaded otherwise.

#30: I’m not sure it does. A lot of the work we’ve done on extended family gifting indicates that people are not going to take a punt on what the child likes and will ask the parents what the child is into, what other stuff they might be getting, etc.

#34: I can see how that would be true in most cases. But it only takes one to buck that trend, and all of your careful selecting is undone: for example, one great-grandmother who sends your daughter this. (She loved it, and it was sent out of love, so I’m not complaining. Just reminded how impossible it is to exercise absolute control.) (Not that I really want to exercise absolute control.)

I agree with this – but I think we’re talking at cross purposes. It will have an affect at the individual level within families (and I don’t think I’d want it any other way – we’re not, nor should we be raising, perfect little automatons, so the happy accident/unpredictable idea taking hold should be encouraged) – and there will be as many stories of outliers as there are kids and families that you’re talking about – but if you’re trying to create any kind of policy to promote a product (itself, as Tom points out, a problematic thing to do), you still need to deal in generalities, which means accepting things like this will happen, that you can’t do anything about it but nevertheless pressing on with the likely most successful route.

Definitely that kind of transference from your own upbringing is a stronger factor now – we have a culture which encourages you and enables you to stay in touch with the things you ‘grew up on’ to a much greater extent than it ever did before. Which creates its own parental dilemmas – you need to be very alert to the extent to which your kids are actually into stuff you are exposing them to, and also happy to follow their own enthusiasms and trust in their own boredom (to nick Mark S’ excellent phrase).

Re: 34, I don’t work in marketing or have a grounding in research, so apologies if I’m teaching you to suck eggs, but I assume that work involves speaking to both the parents and the extended family In my case, the extended family would be convinced they check their gift choices with us, and we would be convinced that they don’t/

EDIT this has been superceded by the intermediate replies

Yes, I wouldn’t want toy manufacturers or marketers to run scared of parents who might be irritated by aspects of their toys, because that would seem to be a total capitulation to the parents’ interests in all of this, rather than the child’s. Another example that comes to mind is a learning drum that some friends gave our son when he was born, explicitly because their son’s one irritated them no end and they were sharing the joy. Sure enough, it was annoying, but he loved it. It may also have helped him pick up numbers and letters faster. It may also be the reason he’s now a proficient drummer. So I don’t for a moment think that we should have smashed it into tiny pieces with a hammer while chanting “Slay the Drum, Everyone, Slay the Drum”. Though the thought may have crossed my mind.

The toys that are more concerning are the heavily gendered ones, because of the baggage they carry. But apart from not buying our daughter a Barbie ourselves, and being fairly confident that most of her extended family wouldn’t, we accept that there are limits to our influence. If she ends up with one, it’s going to be from one of these left-field sources, or from buying it with her own pocket money one day – and if the latter happens, it will be because of the influence of friends (wanting to be able to play like and with them, as you say, Cumbrian) and of the wider culture. It is what it is.

37: I’d agree that the culture is more set up for retention of formative experiences by parents and the potential for passing them on is greater than it ever has been. Companies have spotted this and exploited as appropriate though (just in TV, there’s a number of reasons why the Turtles have come back again, that Dr Who was resurrected when it was, that Scooby Doo is pushed by a number of different kids’ TV channels in its different incarnations and that Disney is making content for its pre-school channel that at least is obliquely linked to their heritage films – but the one I keep coming back to is that the cohort that grew up on a lot of this stuff is starting to have children of the relevant ages themselves).

I’d also argue that this has been going on forever though, just in different ways and that it’s only more visible now. Taking myself as an example, my musical preferences are, at least in part, a reflection of the stuff that was put on when I was growing up – which is the stuff that my Dad and Mum were into (so I prefer the Stones to the Beatles and, following from that, tend to prefer the harder edged to the more mellow – it would have been interesting to go back and see what would have happened to my tastes had theirs been different). It’s the increase in visibility of this which seems to be the main difference between then and now though (itself allied to technology retaining a lot of old content and that companies seem to be actively looking at what was big with kids 20 years ago and rehashing it to try and use this as a point of leverage).

Linked to this, a thought has just flashed across my brain. Is rockism amongst some groups possibly linked to the fact that rock music was the music that they grew up with, possibly because parents exposed them to it at a young age? So they are fighting for the primacy of their formative influences rather than anything specific about the music itself – though it may manifest itself in fighting for the music in the end? What will happen when the children of the trance era have children of their own and, perhaps, pass on formative experiences of listening to this music to their children?

#33 “I genuinely think that the primary audience for Barbie branding is parents but I am willing to be persuaded otherwise.” A tentative observation from me, because this is something you think about a lot more than I have, but I would have assumed that a lot of branding for kids is around that whole age-aspirational phenomenon, where kids aspire to be older than they are, and want toys that code older than they are. The Barbie branding reads to me like an 8-year-old’s idea of an 11-year-old’s world, designed to entice young girls into Barbie play. I don’t get a strong sense of parents as primary audience, but this may be because of the circles I move in, where the pinkification of everything is a concern – plenty of people must not be bothered by that, or contemporary toy stores would never have any adult customers.

There’s an episode of Man Alive from 1967 (which can be found on Robin Carmody’s You Tube channel…unable to link to it at work, unfortunately) which underlines the assertion that some adults, in this case men, continued their boyhood interests well into middle and old age. Using their expendable wealth to make the childhood worlds they created as “real” as possible. So that kind of culture which Tom mentions @37 is nothing new.

It’s almost too much of a coincidence that Robin posted this episode on the same day Tom posted BG on Popular

#41: Firstly, all ideas are welcome. I am not an expert by any means – if I have learned something in my time doing my job, it’s that my preconceptions are wrong more often than not and that the kids/respondents will swiftly kick me in the brain to get me in the right place and anything that makes me think again about something is likely a general good.

I think that there is something in that – though perhaps not for Barbie, I’ll come onto why in a second – as we definitely see that kids have an aspirational view of quite a lot of toys/books/content and so on. A lot of popular stuff for younger kids is based on what happens at secondary/high school (Harry Potter being one example), where they kind of know what is going on or have a good idea at least, and hope that their experience when they get there will be something like what they’re imagining (though in Harry Potter’s case, whilst it might be cool to save the world, this might be based around the friendships that they might have there, putting the bully in his place and so on).

Barbie, from what I understand, tends to be the type of thing that is not aspirational focused towards older kids though. To start with, for the younger kids, it’s probably about replicating the types of things that Mummy does – which is why there are kitchen set, hairdresser sets, you can paint Barbie’s nail, etc – that they can’t do but have seen happen and, thus, is aspirational to her (this then leads onto a number of questions about what Barbie is saying about women in general). Later on, you get into the ages where they make the dolls have sex with each other as Tom points out.

That said, the dolls have to appeal to kids who want to do those sorts of things (i.e. mimic Mum not make the dolls have sex with each other), so maybe some of the branding is aimed at kids (but from my original post, I’m not certain whether this is branding and more about product features – I can take Barbie to her new swimming pool or to the nail bar or whatever – that they might want to help expand their make believe world). This stuff still, typically, needs to be bought by parents/other adults though, so the branding itself probably still needs to assure parents about the qualities of the product. It’s probably not as black and white as I was originally making out.

Barbie is also a storytelling toy, I’d guess (i.e. like any other “character” toy kids tell stories around her) which complicates things in that Mattel lean so hard to promoting a particular kind of aspirational domestic storytelling (I suspect by this point we’re offering crude cave drawing versions of the feminist Barbie theory stuff Tonya mentions upthread, though…)

On Wikipedia there’s mention of a soap-esque example of centralised brand storytelling when Mattel announced that Barbie and Ken had broken up – commencing a long “plotline” about will they get back together etc. This seems a weird publicity stunt – introducing a “central narrative” to Barbie who really doesn’t need one. (I guess it only works because basically nobody gives a fuck about Ken)

I tell you what else Barbie is – the finest mind of her generation. And why would anyone give a fuck about Ken, given what he’s like actually like?

Toy Story 3. Excellent.

I guess, tying in with one of your original points, that the number of ways you can play with Barbie is limited only by the child’s imagination – i.e. they’ll do stuff that the makers never envisaged (and I’m probably not capable of imagining either).

I had a Peaches & Cream Barbie and a Sindy inherited from my sister – they generally took a back seat to the herd of My Little Ponies (talking animals deemed to be more interesting than talking humans) or the GIANT Jem doll (a good 3″ taller than B or S and who turned into a rockstar when she put different earrings on = amazing). The turning point came when one day I realised Barbie’s head came off really easily, and I could offer her and Sindy as human sacrifices to the MLPs (blame a combo of Secret Water and Mysterious Cities of Gold for that idea). Mum was quite alarmed, even when I showed her that Barbie’s head popped right back on again.

Aside from Aqua, Barbie’s best contribution to popular culture IMHO is Joan Cusack’s slideshow torture scene in Addams Family Values. Malibu Barbie. The nightmare! THE NERVE!

Here’s the link relating to my own post @42:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xFjHNMvxrDo

#45: “Authority should derive from the consent of the governed, not from the threat of force!”

(An infinitely better subversion of Barbie as a concept than this song could ever hope to be.)

To most music commentators, irony remains a type of metal, like goldy and silvery. Damning “Barbie Girl” as setting feminism back a millennium is a particularly pointless pastime; Aqua were all about cartoons, as the gleamingly bright blues and whites of the cover of their Aquarium album demonstrate, though theirs was an image in the direct lineage of Zillionaire-era ABC and Deee-Lite rather than the Archies; one which examined the nature of its own artificiality and the unbridgeable chasm between line drawings and lived life. The 78 rpm female lead on “Barbie Girl” brightly chirps “Make me walk, make me talk, do whatever you please” but also notes “Life in plastic, it’s fantastic” and “I’m a blond bimbo girl in a fantasy world.” This is no idle or idiotic submission to submission. Moreover, the gravel-voice lunkhead oaf that is Ken growls “Come jump in, bimbo friend” and “Come on Barbie, let’s go party” without once realising that he is as much of a doll, as artificial a construct, as she. So enamoured were Mattel, manufacturers of the Barbie and Ken dolls, of the record that they unsuccessfully attempted to sue Aqua for brand defamation. Not exactly a ringing brand endorsement.

What Aqua really represented was a Nancy and Lee for the dawning of the New Pop Mk II era; as Abba had rescued pop in 1974, so did Aqua demonstrate that New Pop, not being a finite cage of a genre like Britpop, could have nine lives. On the cover of Aquarium Lene Nystrøm looks like a Swedish Goth, all black mascara and scowls, while René Dif is all goofy shaven headed grins. And the group were their own masters. Demonstrating a sophisticated grasp of post-Pet Shop Boys/SAW nuances and stratagems, their bubblegum swam like eager goldfish striving towards the sun. “Barbie Girl” is fully aware of the constructs which it sets out to undermine – note Nystrøm’s rank laugh of “ah ah ah, yeah” in the bridges – and they set out to drive on the road to nowhere except the other end of the bedroom wall; and yet, through its pop magnificence, “Barbie Girl” transcends its own commentary, or rather enlarges it so that it is the unavoidable centre of its beauteous bounce. After a summer of sternly sombre reflections on death, it arguably tackled the subject of living death more subtly than any of its recent predecessors at number one, and so persuasively that almost despite itself it restored life to the top of the charts.

#33 This has nothing much to do with pop music and the marketing thereof (although, I dunno, maybe it might?), but I can offer a first-hand case study: as parents of a boy (3) and girl (1), parents who confidently and loudly stated we’d never intentionally pressure or steer either of them towards gendered pursuits, and indeed parents who indulged in some hands-on interference to prove a point by buying each of them toys that were explicitly marketed towards (or whose packaging was covered in actual pictures of) children of the opposite gender, nonetheless we watched in bemusement to discover my son almost exclusively favours toy cars and a football, and my daughter almost exclusively favours cuddly pink teddies and bunny rabbits and soft dolls. Many of these things were chosen themselves, some of them were bought for them by relatives, and in several cases they’ve co-opted something of their brother’s/sister’s which wasn’t bought with them in mind, which had lay barely-touched, and made it a beloved companion for a couple of weeks.

(Weirdly, the only area where gendered marketing hasn’t shown a seemingly innate effect (whether it’s really innate, or whether gendered marketing is simply so pernicious it beat our efforts to circumvent it) is storybooks, especially Disney tie-in ones; my son’s just as happy reading about Cinderella and Tinker Bell as he is with Cars and Planes. My daughter mainly just wants the one with the most easily chewable content, I’ll report back when she’s older.)

#49 Marcello, who/what is your first paragraph reacting to? I don’t remember too many accusations of anti-feminism at the time (probably because as a tedious indie kid student in 1997, I wasn’t looking), and there’s only one reference upthread to a critic who made a face value reading of the record – was that a widespread thing that happened?