In the 12 years since Band Aid, the charts have hosted a lot of charity singles – more than enough to give you a cynical familiarity with the shape of them. A terrible thing happens; the public is horrified; a number of pop stars make themselves available to help – some selflessly, some perhaps not; a sombre track is found and a dirge of a cover recorded; Number One is reached; the proceeds are (we trust) distributed; the matter is closed, and if any good is done we do not hear about it. The Dunblane single is almost completely different from any of this.

In the 12 years since Band Aid, the charts have hosted a lot of charity singles – more than enough to give you a cynical familiarity with the shape of them. A terrible thing happens; the public is horrified; a number of pop stars make themselves available to help – some selflessly, some perhaps not; a sombre track is found and a dirge of a cover recorded; Number One is reached; the proceeds are (we trust) distributed; the matter is closed, and if any good is done we do not hear about it. The Dunblane single is almost completely different from any of this.

The background: in March 1996 a terrible failure of a man walked armed into a Scottish primary school and murdered sixteen children and one adult. In the aftermath of this atrocity, public disgust and general political will made some kind of handgun ban inevitable. The question was – how far would it extend? A commission made recommendations which the waning Conservative government accepted: most handguns would be banned. A petition, circulating since the massacre, argued for stricter legislation: outlaw all handguns. As of December 1996, however, this was not on the table.

If the Dunblane massacre had been the kind of tragedy to inspire a standard charity single, we can imagine what it would have been like. It would have charted in May or June, with the horror fresh in public minds. It would have involved a number of Scottish stars – Marti Pellow if available, certainly a Proclaimer or the fellow from Del Amitri. It’s entirely likely “Knockin’ On Heavens Door” would have been the song.

It sounds – and would have been – obscene. The charity single we did get is not, because Dunblane was not that kind of event. The reporting of these crimes – honed by the British press with the Hungerford massacre in 1989 – takes place first at a horribly intimate level, tracing the murderer’s movements second by second, step by step, death by death, using maps and photos to tempt the reader into imagining what the mind wants to flinch away from. After a few days of this the media zooms out, and focuses instead on the aftermath. How does a family cope with the murder of a child? Nobody wants to see or show the real answer to that (“it doesn’t”) so instead the story becomes how ‘the town’ or ‘the community’ deals with it. Mostly the community wants the media to get the hell out, and the story begins to slip away.

There is nowhere into this schema for music to fit, no celebrity response that wouldn’t seem like the most grotesque exploitation. But “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” invents a place for music, by taking the media’s prurient interest in ‘the town’ and making it tangible. The record is credited not to some one-off team, but to ‘Dunblane’ – the single is by and from the community, not just for it. This was genuine, to some degree – Ted Christopher, the musician behind the single, put together a band of Dunblane musicians to play (Mark Knopfler helps, but to lend professionalism as much as star power). The children’s choir on “Throw Those Guns Away” even includes classmates of the murdered kids. However sentimental the end result, this is an attempt at catharsis, not the kind of pat closure I’ve criticised on other event-led charity hits.

“Throw Those Guns Away” also points to the other thing that makes the Dunblane single unusual. It is an explicitly political charity record – perhaps the most focused political Number One ever. Most charity hits obscure the controversy and political wrangling that comes in tragedy’s wake: not so Dunblane. It is a specific intervention in an ongoing policy debate, a petition as much as a record: all handguns should be banned. Tony Blair adopted that policy, and it was law within six months of New Labour coming to power. Now, it’s not likely Blair adopted the policy because of this record, and the single isn’t taking a difficult or unpopular stand. In fact it was the kind of emotional open goal his opponents were regularly terrible at spotting. But the massive response to this single – nine months after the massacre – would at least have confirmed his instincts, and helped cement the policy as part of the UK political consensus. Nowadays, only Nigel Farage makes serious noises about loosening the handgun ban.

In the end almost none of the standard objections you might have to a charity single apply here. It’s no celebrity junket, it’s a genuine response by (some of) the people affected, it’s pointedly specific in its demands, and it’s about its events in a way nothing since Band Aid has been. Its very success in those areas makes it virtually unlistenable – alone in the charity hit ledger I can’t hear it without thinking of what prompted it. Really though, the only thing it has in common with other charity hits is that the music isn’t any good. For once that doesn’t matter: this is as close to an unmarkable record as I’ll see. It gets an arbitrary number: these songs did the job they set out to, and now I will never play them again.

Score: 6

[Logged in users can award their own score]

RELATED POSTS – MR BLOBBY – “Mr Blobby”. Does the algorithm have some sort of pro-gun political agenda to push here? (Sorry for the silly first reply, this might turn out to be a fairly serious thread.)

New Popular post on the limits of charity records and the borders of political pop. http://t.co/TYNDjL3hEv

I put my farewell to Pete Seeger under Mr Tambourine Man for want of anything better, but I suppose as the epitome of political pop he could well go here too.

I suppose it might be too much to hope that Andy Murray sang on this.

Indeed Andy Murray did not sing on this but the near nine-year-old was alas present during the massacre, taking refuge under a desk. Not surprisingly, he does not talk about it today. His mother Judy knew Thomas Hamilton quite well and doesn’t talk about it either. The whole thing must have been dreadful for them both.

For all this was notionally a double A-side, “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” was very much the lead track in terms of radio/TOTP etc., right? I remember little if nothing about “Throw These Guns Away”, in any case, and the Turkish cover version on YouTube offers only limited help…

according to wiki John Major’s government introduced the original Bill banning the ownership of handguns except for the smaller caliber .22 guns. The new Labour government introduced a bill that banned those as well.

My dad owned a couple of guns that he used for target shooting and had to give them up. He wasn’t best pleased about it. I’m ambivalent about the decision. Incidents like Dunblane were extremely rare in this country and the new law appeared to be a case of politicians playing to the gallery. However, it may have created a safer country.

As for the record, the original KOHD benefits from being short. Subsequent covers always tend to drag it out, emphasising its maudlin qualities. This throws in Psalm 23 and a kids’ choir as well. Good cause, poor record.

Just to put a hypothetical cat among the pigeons; how would people feel if this song had been successfully campaigning for the reintroduction of the death penalty rather than the banning of handguns? Not sure if this is a realistic proposition as it would require a different kind of narrative, but it’s not impossible to imagine.

I remember being very cross about this record for both the usual reasons & because I thought the law was pointless in safety terms. The community connection was something I hadn’t considered as a distinguishing feature before, so ta for that extra perspective there Tom.

Due to the corporate firewall, I shall comment further on this once I have listened to both tracks.

Weej’s counter factual question is a very good one – the point is that pop singles aren’t generally expected to be politically effective: this offers a new way for how charity records work, and one I think is admirable, but it’s a way that repeated at scale would break the charts.

So in that sense my rating for this should be a reflection of the political position it supports – and it’s not, because I don’t have a thought out position on the specific difference between the Tory and Labour handgun bans in 1996. I like living in a culture where impulsive gun violence is rare and made more difficult by law. On the other hand the law didnt actually change the gun homicide rate long term and it’s also very clearly the first step in New Labour’s emotional appeals to public safety as a cover for authoritarian laws.

I can’t hear it without thinking of what what prompted it prompted.

I flew home to Tasmania on Sunday 28 April 1996 for a job interview the next morning. Switching on the news in my hotel room that night, I saw an old school friend, a nurse, meeting ambulances at the Royal Hobart Hospital, where victims of our Dunblane-inspired massacre were being taken. At that point the killer was still at large. He had shot 58 people, killing 35, in and around a popular tourist location that I and every other southern Tasmanian had visited many times. When I read descriptions of the events in the cafe and gift shop (since demolished), I can visualise the rooms.

In an email earlier that week my parents had said they were thinking of going for a drive down there on the weekend. I spent the night wondering if they had.

I was a bit subdued in the interview, and didn’t get the job. Mum and Dad had driven to Port Arthur and back on the Saturday. Several years later, they moved to a town nearby, and I’ve visited the area many times since. Fortunately, the place has taken on a new significance for me.

Australia passed strict gun laws in the wake of Port Arthur, and bought back and destroyed three-quarters of a million guns, including the air-rifle my Dad had taught me how to shoot as a teenager, and the vintage rifle he had inherited from a 19th-century ancestor. I don’t lose any sleep over that; there are other family heirlooms, and what the hell would I or my brother have done with it. If we compare firearm mortality rates between 1996 and today, around four or five thousand gun deaths have been prevented in Australia as a result of those laws.

I’ve passed through Dunblane, on a cycling trip to Loch Katrine a decade ago. Now that I’ve got a son of my own in primary school, I can hardly bear to think about what happened there.

I have no idea what to give this record, and can’t find the less-famous track on YouTube to judge. The additional lyrics to “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” are jarring next to Dylan’s, authorised or not, and the performance is nothing exceptional. But the lack of celebrity guests is refreshing, and the notable exception of Mark Knopfler on guitar makes perfect sense on a Dylan cover. The musician behind the single has remained committed to the cause, travelling to Tasmania, America and Turkey to support families of victims and campaign for gun control, and deserves credit for his efforts. I think I’ll give this 5.

Likewise, I only remember KOHD from the time and can’t find the far more interesting sounding side on youtube. Does anyone have a link to it?

As Rory at 11, Cumbria has had its own brush with gun violence, and, as with Rory, I spent a (thankfully very brief) amount of time wondering whether my Dad was anywhere near the incident due to his travels around the county (he wasn’t). Nevertheless, when something like this happens in an area you know, it does make a difference in some small way; it all becomes less abstract somehow – even if you are not involved personally in any way and, at least speaking for myself, can’t really appreciate the terror and then the grief that the families go through when these events happen. Anyway as a result of the now slightly less abstract nature of the shootings for me, doing the reading around this and listening to the record (KOHD – still can’t find TTGA online), whilst not actually in tears, I could feel them prickling the back of my eyeballs.

I’d go further than Tom and say this record actually is unmarkable – but then I am not committed to having to put a mark at the end of my comments, so I can appreciate why Tom did give it a mark and found rationale to do so. Fortunately, I don’t have to, so I’m simply not going to mark it.

On a different note, though still dealing with gun violence I suppose, I’ll say that “Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid” is pretty good. I prefer it to Peckinpah’s more lauded other works at least (definitely PG&BTK for me rather than The Wild Bunch).

And on KOHD, I’ll open myself up to accusations of blistering cock-rockism by saying my favourite version is the Guns N’ Roses version. Axl revving himself up from his growly voice into full cry – possibly his most thrilling vocal moment.

These last two comments possibly well besides the point. Apologies, if so thought.

Um sorry if the review made TTGA into some Rosetta Stone you need to fully understand the record – it’s not: the title pretty much says it all, and musically and emotionally its very much a cousin of the extra verse on KOHD.

I wasn’t expecting a revelation Tom, but it’s a rare charity single that doesn’t plump for a (very loosely in this case) relevant cover. On musical terms KOHD isn’t good*, and I don’t feel I want to give Dunblane preferential treatment over other human tragedies. So I’m intrigued to hear the other side, and can’t get this single into perspective without knowing how it sounds.

*The cause aside, I’ve always found the song to be a huge drag, closer to Eric Clapton’s work in the 70s than Blood on the Tracks.

I have to agree that in essence this is ungradeable: I don’t think the music is actually “bad”: it’s just what you might hear in a pub on a Friday evening in a small Scottish town – like Dunblane. Straightforward enough, ordinary enough with no whizzo artistry or expensive effects. Which is precisely why, in so closely recalling the acts of evil that inspired it, the record succeeds in tugging so strongly on the heartstrings, as it does. One might call it manipulative, if one were looking to be harsh: but I find it still an extraordinary act of remembrance, with the “political campaign” aspect being quite secondary to that.

(Horrific TOTP presentation of Sean Ryder presenting the group when they were at no 1 on Youtube, and then returning after the song, with a tinsel wig on, describing himself as “Junior Jimmy” – I think we know which one)

Also, a small correction: the Hungerford massacre was in 1987.

For those who wish to hear “Throw These Guns Away”, I just found this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zsm6dheb-gY It’s the second track played.

I will be making my own comments on this single and its subject once I have time to collect my thoughts.

#15 I don’t think it’s a case of giving Dunblane preferential treatment – Dunblane really is a different kind of event from the ones that usually get charity records. In fact a criticism you can make of records like Band Aid and “Ferry Cross The Mersey” is that they reduce the avoidable consequence of actions and policies to a kind of ‘natural disaster’ status. That isn’t possible with Dunblane and my argument is that by putting an (arguable) cause as central to the record – and by rooting the response in the community and culture affected – it achieves an integrity most charity records miss.

I agree that KOHD is a weak song, and it’s annoying that it’s probably Dylan’s most busker composition!

Busker-friendly, sorry

Thanks Mapman132, that’s really helpful. Listened to it just now, and found it even more affecting than the KOHD cover, for the reasons Chelovek na Lune gives.

#7 The death penalty argument would be completely inappropriate given that Hamilton executed himself.

TTGA sounds a bit like it could have been by Neil Young (and I like Neil Young – I offer this as no positive or negative criticism of either, merely an observation).

The extended scene in Peckinpah’s uncut Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid:, or as near uncut a cut as we are likely to get of that least tangible of films, where Slim Pickens' exhausted, shot sheriff takes his time to die, slowly blending with and melting into the river, the rugged terrain, the past, finally drifting away, as though solidifying into sepia, to the soundtrack of Dylan's original "Knockin' On Heaven's Door" is one of the most sheerly beautiful sequences in all cinema, seeming to bid a bleeding farewell to goodness and mobility. Yet we have to be suspicious of applying nouns like "beauty" to what could from another perspective seem a bewitching romanticisation of violent death; the sort of groin-tightening allure which inclines unstable people towards owning and using guns.

If you travel northeast by train out of Glasgow's Queen Street Station you will pass Dunblane en route to Stirling; a quiet, tidy, unassuming, solvent village much like the one where I went to school and grew up. One Wednesday morning in March 1996 a frustrated middle-aged scout leader and gun club member named Thomas Hamilton walked into the first year gym class of Dunblane Primary School with two Browning pistols, two Smith and Wesson revolvers and an estimated 743 cartridges of ammunition and opened fire, killing fifteen children, all aged between five and six years, and one teacher. He wandered around the school firing some more shots, particularly through the door of a Portakabin into a class where the children were obliged to hide under their desks for protection. One of these children died from their wounds; the young Andy Murray took refuge under another desk, in the headmaster's office. Hamilton finally returned to the gym and used one of his revolvers to dispense with himself.

The outcry started almost ahead of the grieving, and vigorous efforts by the victims' families eventually ensured, with the advent of the Blair administration the following year, that handguns were legally outlawed. But how difficult is it, short of total totalitarianism, to militate and regulate against the chance that a distressed societal outcast with decades' worth of pent-up frustration and perceived feelings of inferiority will one day opt to take brutalist revenge, to ensure that people remember his name? As the 1987 Hungerford massacre – in which my erstwhile parents-in-law were exceptionally fortunate not to get mixed up; it was their habit to travel into Hungerford on Wednesday afternoons for shopping, but on that particular Wednesday my then mother-in-law was feeling under the weather and so the trip was cancelled – confirmed, Columbine-type scenarios in Britain will tend to be inaugurated by "grown" adult members of the community, their long-term smouldering resentment finally igniting.

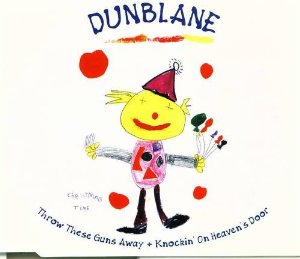

Ted Christopher, a Dunblane-based singer/songwriter, organised a charity record to help with the anti-firearms petitioning, and also arranged for its proceeds to go to various children's charities, including Save The Children, Childline and the Scottish Children's Hospice Association. He chose to couple a revised version of "Knockin' On Heaven's Door" with his own "Throw These Guns Away." Dylan gave his personal consent for Christopher to alter the lyrics and, in tow with a group of pupils, all brothers and/or sisters of the victims, recorded the single in Abbey Road Studios, sometime Dylan collaborator Mark Knopfler helping out with lead guitar, arrangement and production.

The Dunblane "Knockin'" is a numbingly raw listening experience. The original could also be seen as a postponed farewell to the ideals of '67 (with Roger McGuinn also appearing on guitar) and given that calls for revolution in '67 frequently involved the open citing of guns in the street, this recording helps close an extremely sad circle (since this is what ends up happening when you let people walk about with guns on the street). Christopher's hoarsely passionate lead vocal owes rather more to Guns N' Roses' somewhat overwrought 1991 reading, though Knopfler is very careful not to let the music turn hysterical. The lyrical alterations are clumsy but burn with an unavoidable fire: "So for the bairns of Dunblane," Christopher intones, "We ask please – NEVER AGAIN," those last two words sounding as though he's ready to blow his own head off. There is an interlude where Psalm 23 ("The Lord Is My Shepherd") is invoked, and then the children's voices, unruly, defiantly Central Scottish, waft into the mix like ghosts; it is a chilling moment. Christopher sings of the exhaustion and slow death of goodness in the manner of someone who can no longer fend off savagery and devil take the hindmost – at the very end he sighs, rather curiously, "I've been there too many times before." "Throw These Guns Away" can't and doesn't compete with Dylan, but voices many of the same intended sentiments ("Lost familiar voices softly whispering in the wind/Pleading that this time we will hear") in an easy singalong format.

This is one of the most uncomfortable number ones to assess, given that I was born and brought up in Scotland and that this event touched everyone in Scotland (except for pro-huntin' and shootin' and fishin' idiots like Sir John Junor who fulminated that the Dunblane campaigners should go to hell; happily he himself did so shortly thereafter); it defies concepts such as critical analysis, since the execution is imperfect but the emotions could scarcely be less real or palpable. And, as more recent spates of shooting and worse have confirmed, the addressing of the circulation of firearms in those connected with organised crime is a far thornier issue. For now I will merely note that the act responsible for the next Popular entry obligingly delayed the release of their next single to allow “Knockin'” a fair run at the top, and that for once this is too, too personal a situation to despoil with a rating. I think it’s ungradeable, which in this context I will translate into not giving it a mark.

Thanks Mapman. Throw These Guns Away is pretty affecting – a simple structure and arrangement, pitched between Neil Young and Van Morrison, which avoids sentimentality and swaps gentle reason in its delivery for the uncomfortable/unlistenable raw vocals on KOHD. The lyric’s directness and chanted chorus remind me of Give Peace a Chance.

Like Give Peace A Chance, this is a straight protest record, which makes it a very different thing to other charity singles. It has one direct political objection, rather more achievable than GPAC – the fact that the proceeds went to various children’s charities seems quite incidental.

I agree that that it isn’t like any other ‘charity’ number one, because it isn’t one, though that is certainly how I (and others?) perceived it at the time – an easy enough assumption when one side is a melancholy over-familiar song in the same vein as Let It Be, You’ll Never Walk Alone or Ferry Cross the Mersey.

Does anyone remember hearing Throw These Guns Away on the radio, ever?

I can remember exactly where I was when I heard the news of the shooting, but that isn’t really important; this song is unrateable for me, for much the same reasons as it is for others who have already and more eloquently commented, plus the fact that the town of Dunblane is a bit too close to some members of my family.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, opinions were voiced that if the teachers and/or children had been armed themselves, none of this would have happened. Your mileage may vary.

I was going to mention something about guns and the pop landscape, but there will be a more apposite #1 in 1997 to discuss that, somewhat distant in time and space from Dunblane. There’s nothing useful I can add to this discussion, other than add that my preferred reading of KOHD is the G&R version.

Having heard both songs, I feel I have no desire to hear either of these recordings again in my lifetime.

Due to the subject matter and my strong opinions on it, this is the first Popular posting I’ve edited on and off over the course of multiple hours rather than written and posted all at once. I’ve tried to convey my thoughts as accurately as I can without going overboard, so here goes:

The Dunblane massacre was news in the US in 1996, as were the subsequent events in Port Arthur. As everyone here is no doubt aware, gun violence is sadly an everyday occurrence in America, and I’m not just referring to the large scale events that make the international news, but the regularity of homicides, suicides, and fatal accidents (often involving children) that would simply not occur if not for the presence of guns. Fortunately none of my close friends or family are gun owners and I live, work, and generally travel in safe neighborhoods, so I have no real fear of being victimized in my personal life. But many other Americans aren’t so lucky.

I don’t need to go one by one through the long list of American massacres in recent years to explain why I’ve grown somewhat numb to them. But 2012’s tragedy in Newtown, Connecticut shocked even me. Perhaps it was the young children victimized or the fact that I was already dealing with a (non-gun-related) tragedy close to home that week, but Newtown affected me as much as any news event since 9/11. And worst of all, it was completely preventable.

The sentiments expressed in the Dunblane record are therefore pretty much what I was feeling in the wake of Newtown, with the fortunate (for me) exception that I didn’t live in the affected town(s) and didn’t know any of the victims. The fact that the performers were very close to the events washes away the cynicism that I sometimes feel about a post-tragedy record and makes for a very poignant listen.

However, what takes this record from total sadness to at least a feeling of hope is the knowledge that the UK learned from the tragedy and has taken steps to prevent it from happening again. While these steps may not have eliminated the problem entirely, it’s far, far more than my country has done. Obviously, I have much less feel than most on this forum as to whether this single had any direct effect on gun control accomplishments, but it certainly doesn’t seem to have hurt.

I considered going on a rant about the state of gun politics in the US, but that seems well outside the scope of this blog. So I will simply say that Britons and Australians should feel proud of having the political willpower to effect real change in the wake of their respective tragedies. Undoubtably lives have been saved. I wish that I could say the same of my own country.

I’m going to vote for this in the year-end recap, but agree with others that it’s essentially ungradeable with an actual number.

I can’t.

I mean, I really want to. But this disc sums up everything that I hate about charity records – it bludgeons you into agreeing with the cause and makes you out to be a heel if you don’t. This feels like one of those RSPCA adverts you always see every year at Christmas (the timing of the release of this record is not coincidental). And I find them to be needless attempts at manipulation that just roll off me too.

The fact that it’s not technically a charity record makes scant difference; if anything, it makes it worse. Law and politics are hard and there’s a reason why our elected representatives are cold and calculating rather than emotionally hysterical. Gun politics aside (broadly speaking – I’ve never handled anything more powerful than an air rifle and nobody in my family or social circle has ever been affected by gun crime), populist knee-jerk reactionary policies don’t typically result in long-term success.

The record doesn’t help, because it starts a horrible, horrible trend; that of the sob story being more important than the record. Granted, it’s one hell of a sob story this time round, but the makers of this record are asking us to vote for the singer, not the song. The coming decades of Popular – particularly later Christmases – will show us the issues with that path.

Maybe I thought it was too far away. Maybe I was watching something else. Maybe I was too old. Maybe I’m just cynical (16 year old me was very cynical and 33 year old me remains so). In a few Popular years’ time, my region of the country *will* reach the national press with a story about a man with a gun. Nobody will make a song about that.

The massacre at Dunblane was a horriffic event, perpetrated by a madman at the end of his rope, who would have done what he did even with a handgun ban; and I’m incredibly sorry for those whose lives were personally affected – those who knew the people, the area, the time, those who even sung on this record. Watching Andy Murray struggle to talk about it with Sue Barker and his dog was a truly harrowing experience. But the number of people who say this record is “ungradeable” tells the true story; it’s rubbish of the highest order, but we’ll all feel like bastards for saying so.

1.

#27 Thanks for the eloquent post (and thanks to everyone else, even when I disagree, for some heartfelt responses). I basically think there’s almost nothing useful anyone outside the US can say about US gun politics, so I’ll say nothing.

#28 I did grade it, so I’ll let others take you up on your interpretation of “ungradeable”. But as for letting the ‘sob story’ sway the song – first off, that ship obviously sailed a long time ago, it’s the principle not only behind every charity record but behind every posthumous hit and most protest songs. And one of the themes of Popular (as I pointed out on one of the sidethreads a while ago) is that if you want context to count, it counts. Pure just-the-record-please listening isn’t generally possible or desirable.

“Free Nelson Mandela”, for instance, is a sob story. “It’s a good song, though”, someone might say. But that’s not the point – it’s indivisible from its context, assuming the basic knowledge of who Mandela was. There is no magic non-contextual version of “Free Nelson Mandela” which could be subjected to purely aesthetic judgement, any more than there’s a non-contextual version of Dunblane which is “rubbish of the highest order” until you bring all that sob story content in. The artificial, ‘manipulated’ reading of any song is the one that tries to strip out its context as much as possible, not the one that allows it in.

(I’m not saying you’re not allowed to dislike it, of course – and the rest of your post is full of entirely contextualised reasons! I just don’t think “this is bad because people were buying it for X not the song” is ever a strong argument, even if it’s almost impossible not to reach for with stuff you detest)

#28: I take the argument, and I broadly agree with it; you mentioned posthumous hits, usually rereleases of earlier work that came back out because the artist happened to be in the news, and ultimately my problem with them is similar; if it’s not new material (which, you know, “posthumous”; unless it’s Tupac, of course) then it’s serving no purpose. I’m (keenly?) anticipating interesting reviews of several posthumous bunnies in the years to come – particularly those that we’ve already met – and seeing how the analysis will come any further than my gut response of “Why?”.

Protest songs as a genre are, I suspect, a thing I’ve just never Got. Wrong age, wrong time, wrong place, wrong something, I suppose I didn’t have enough to complain at. Some might say I’m incredibly lucky in that regard, and doubtless they’d be right. (A much later bunny was clearly on to something, talking of a whole generation with nothing much to complain about…) But a protest song needs to be able to hit the listener in the right place at the right time, and so far none have really managed it. Nelson Mandela didn’t – I was three at the time that was released, I barely had any idea that it even existed, never mind the subject matter it was protesting. (Not picking on Nelson Mandela itself – it’s clearly pretty good, if surprisingly upbeat for a sob story of a song, as opposed to the dirgy covers you mentioned up top – more about my personal ability to contextualise any given track.)

For the context of any protest or posthumous song (or any other song, for that matter) to matter to the listener, there has to be some way for them to personally and directly connect with it. This is why I loved Three Lions, why Tales From Turnpike House is my favourite St Et album (and damn near my very favourite album), etcetera. Without the context it’s just song to me, and when the context overrides the song completely it can’t help but rankle.

In later times (on the Popular timeline), we’ll meet the reality TV model, where a decent sob story as backup will be part of whether a song gets to exist at all, and eventually even Simon Cowell will claim to be sick of the idea. Mix the children into this record, strip away the context of the event, and I’m left feeling like this is the meeting place between The X Factor and There’s No One Quite Like Grandma.

That’s an artificial reading, of course. But that’s the context that counts for me.

MikeMCSG @ #21 – Yes, I’m perfectly aware that it isn’t applicable in this case, that’s why I said it would need “a different kind of narrative.” – but the conversation has come around to the same point anyway, that if the purpose of a song is to use emotions (I don’t like the term “sob story” and it seems quite inappropriate in this case) to put forward a political message then your response depends on whether you agree with that message rather than whether you like the song – that’s why it’s basically ungradable. Of course we could also object entirely to the use of emotion in politics, or the intrusion of politics into music, and on the other hand there’s the argument that everything is political, and that being open about it is healthier than hiding it – but the point remains that the music itself is here reduced to a side-story – the context and the message are basically everything.

A very hard song to review and a near impossible one to rate. Viewed dispassionately it does have some interesting chart markers – Mark Knopler’s only involvement with a number one singles and (I think) the first Bob Dylan composition to hit the top since The Mighty Quinn in 1968 and the last direct cover to do so (KOHD would return as a sample but I bunny).

A few recent threads have touched on Toni Braxton’s massive American chart-topper Unbreak My Heart which had spent a good few weeks touring the top five and, during Dunblane’s week at the top finally rose to number two – it would return there two weeks later on the dead end of year chart.

During the chart run down Mark Goodier always used to play the dance remix of Unbreak My Heart which annoyed me and I remember a contributor to The Vibe on Ceefax (God I’m showing my age) accusing him of `inflicting his narrow minded musical tastes on the rest of us`. Goodier once commented – possibly defending himself against similar complaints – that the remix was the version selling the record. I’ve wondered if this was fair comment.

I don’t agree that this is “ungradeable” (for all that I did in fact give it a, pretty decent, grade) because of the use of emotions to put forward a political message, as such: would, for example, “Strange Fruit” be ungradeable on those grounds? (I think one can still draw a line between “manipulation” – to be deprecated – and a more measured use of emotion – to engender fellow-feeling – , regardless of whether one agrees with the message being conveyed or not: the (post-Internationale) Soviet national anthem was a cracking composition, even if the uses to which it was put were often more to do with…well, cracking heads, be that, less frequently, physically, or, more commonly, psychologically.). And one can readily enjoy or approve of some totalitarian architecture (oh! for the square Colosseum at EUR on the edge of Rome) without being necessarily converted to the ideology behind the aesthetics…

It is rather the rawness, the closeness to the horrific event, that the record commemorates, that makes it such.

For me, it’s ungradeable on the basis that despite looking like, sounding like and having the trappings of a pop record, it’s actually the de facto petition that Tom refers to his review, just one that is more easily able to go viral in the specific period that this happened. I don’t think a record specifically like this would exist in this day and age – more likely someone would start an epetition at the relevant website and things would go from there.

I don’t think other charity records behave in the same way. Yes, the money from this went to charity, like the others, but I don’t think that was the point. It was to say “this many people bought this record, which is explicitly arguing for this specific action. Count them too”. Other charity records make, imo, some play at being entertaining. This isn’t making that play, I would argue. As such, it shouldn’t be graded on entertainment, which, in my view, is largely what the mark scheme for Popular is about.

No, it’s certainly not “entertainment”. I was wondering further if it should even be categorised as any relative of “art” (which label I think is perfectly fitting of the more high quality outposts of popular culture that we occasionally get to discuss here) – – because of the implication in “art” of “artifice”, playfulness, pretence, even intellectual detachment (which cleverly done can even strengthen the expression of an intended message – as our shiny suited totalitarian antecedents knew too well) : there are absolutely none of these things here, and no room for them here.

(This is separate from another, but related discussion, that would remove the record from all context and discuss it on purely musical terms – is it “craft” rather than “art”? Or does one have to be irredeemably lost in the 19th century to make such distinctions? And do they apply to subsequent, say, seemingly mass-produced items of dance music that we will encounter in years ahead, too….it’s a long way from William Morris to those bunnies, but maybe it’s a journey worthy of consideration)

Personally, I think ‘grading’ is a lot less interesting than the conversations usually generated by Tom’s posts.

This is arguably the most successful protest record in history – that’s a real achievement. Craft rather than art… that a renowned guitarist has been drafted in, and that an appropriate and moving fiddle line gives Throw These Guns Away its flow and emotional feel, that surely makes it art.

Chelovek’s point about Strange Fruit is a very good one – and I’d have given Robert Wyatt’s Strange Fruit/At Last I Am Free a 10 if it had troubled Popular.

Re Kinitawowi@30: “if it’s not new material (which, you know, “posthumous”…) then it’s serving no purpose.”

No purpose for whom? Surely it is new material to the audience making it a hit. Few if any people who already owned “Imagine” would have bought the single after John Lennon’s death, and few of Michael Jackson’s original fans would have bought the compilations of his hits after his. It’s being bought by a new audience hearing the music for the first time, thanks to the exposure it gets from stories about the artist’s death or some other event that brings it to everyone’s attention.

I’ve done it myself. When Elliott Smith died I read a lot about him, got curious about the albums I hadn’t heard beyond XO and Figure 8, and ended up purchasing his entire back catalogue. You might say those purchases served no purpose, but they did for me; for a start, my favourite Elliott Smith albums are no longer XO and Figure 8. If he had been a Madonna-level star instead of an Elliott Smith-level star, those same purchases might have helped create some posthumous hits.

This effect will surely only increase in the digital download era, as every individual track is now immediately available for the newly curious to buy, and (to put it bluntly) there are a lot of big music stars yet to die. No need now for a record company to press up a new run of singles to meet demand.

Or maybe some of Jackson’s old ’80s fans had lost their copies of “Billie Jean” and “Beat It”, and picked up a Best Of after he died out of nostalgia, having been reminded how good they were. That’s not “serving no purpose”, either. That effect is likely to diminish, though, once all music collections are digital – our old loves are likely to linger in our mp3 libraries, because who has the time to weed them out, and they’ll be waiting for us when we want that nostalgic fix in future.

Yesterday, I felt unable to contribute anything useful to this thread. Today, I’ve given it some thought…

Was it a couple of years back, Tom posted something on FT re: difficult listening? In that context, this #1 is excruciating, precisely because of the emotional heft of TTGA and being invited to remember the children of Dunblane were slain for no reason. Additionally Port Arthur, Columbine and Sandy Hook when they happen, the media usually only asks us to view these events in isolation from each other. What TTGA does now is bring all these events and ones I have failed to mention, into sharp focus and it’s message is far too powerful a message for me at least, who was profoundly humbled by listening to 2 songs on a YouTube clip. Dunblane is the very essence of difficult listening.

[Shifted my comment into my one above.]

#35 Well this is kind of the whole background concept of Popular – in creating a chart of top-selling records, the NME (and subsequently everyone else) accidentally invented a space where a whole lot of different uses for music could overlap (and sometimes clash) – dissolving any art/craft etc binary, or at least making it not-that-useful as a filter. So as well as a tour of genres, generations etc. it’s a set of answers to the question “why might people buy music?” as well as “why might artists want people to buy it?” (sometimes less interesting, sometimes more).

Re. “manipulation” – the main reason I don’t think it’s that useful is that it tends to be something that only happens to other people – it’s like how people tut-tut over other people’s ‘irrationality’ and don’t really think about their own biases.

This particular record doesn’t strike me as ‘manipulative’ or ‘artificial’ at all but to some extent its intentions are suborned anyway to the wider media coverage of both the tragedy and its aftermath, which it’s hard to argue isn’t on some level detached or created in a sense of artifice (to use Chelovek’s definitions), just because that kind of selectivity is what media and news DO.

#35: I feel I am on very shaky ground when discussing these sorts of philosophical questions (I’ve done just enough study of Philosophy when at uni to feel really uncomfortable about saying stuff in these broad areas without having a bloody good think about what I am saying and why I am saying it), which is principally why I grounded my thinking on this in terms of “is the point of this to be entertaining?” My initial reaction is probably closer to Lino’s that it is art, inasmuch as, to pick only one of the things you’ve mentioned, there is some intellectual detachment to the making of the point – getting Knopfler in to help add form being one expression of this, rather than just bashing it out and hoping for the best.

As I said though, my thoughts on this are very far from fully formed and I could be easily swayed by persuasive argument one way or the other.

#36: I would agree that the conversation is more interesting than the mark.

Excellent point, thefatgit @38 – it’s a cumulative effect. But even in 1996, Dunblane and Port Arthur built on earlier examples (in Australia, we had the Hoddle Street massacre in 1987, which messed with my head when I lived briefly in Melbourne because it’s a major arterial road I needed to drive on all the time). If the 1996 events in the UK and Australia had been isolated ones, I’m not sure the moves to greater gun control would have been as swift.

#40: I’ve said elsewhere and repeat here that manipulation is not that useful a word. Quite a lot of the best art is manipulative, in that it is designed to try to make you feel a certain way about things. The question is whether you mind being manipulated in that way or not. I don’t see many people minding being encouraged to care about what happens to George Bailey in “It’s A Wonderful Life” for instance, but it is surely still manipulative. Frankly, in my view, it’s a loaded word that is only really used when people mean “I can see what this is trying to make me feel and I don’t like it”.

It’s a crap word, but the “I don’t like the sense of being expected to feel something” vs “I am happy to be carried along” is a reaction worth exploring – so it’s a crap word because it reduces the reaction to a word rather than encouraging people to dig in a bit more.

I would agree with that and why the word is crap. More efficiently and elegantly expressed than I managed, which is probably why you’re the writer and I am the commenter.

#35: if the high quality stuff is art then surely so is the low – bad art is still art.

#37: While I agree with disagreeing with #30 (by any standards, any record that pops up here serves a purpose for a lot of people), I’m not entirely sure about the examples you’ve picked: there’s a lot of different ways to be a Michael Jackson fan: not a lot of people who’d have bought Ben, quite a lot of people who bought Thriller, an awful lot of people who wouldn’t necessarily have thought of buying his albums simply because he was so omnipresent in pop culture. To be a little ghoulish, the posthumous hits compilation is generally the definitive one – no “we stuck their new single in to get them back in the charts”, no “oh he’ll have one more big hit after this from a duff album”.

#46 Perhaps, but surely a distinction can be made (even on something approaching objective grounds – rather than purely on grounds of “taste”? – and even in material that is intended to be part of popular culture) between something that constitutes “art”, something that constitutes “entertainment”, and something that combines elements of the two?

(I think this is something that recent, and especially New Labour-supported approaches to art and the role of culture in public life have tended to get wrong, precisely by overplaying the “entertainment” aspect – familiarity being emphasised over the cerebral or potentially challenging – this is seen above all in works of “public art” that have no real meaning or substance but are intended to distract or raise a smile but no deeper engagement – I cannot be the only person here to be familiar with the Giant Fish of Erith (http://www.drostle.com/erith.html) : the debacle of the short-lived “The Public” art gallery in West Bromwich (which in reality, IMVHO, contained little stuff that might actually be reasonably defined as art – interesting artefacts, yes), is another example, but there are countless others. (probably the first incarnation of the Millennium Dome, too…) The idea of art as a focus of state-directed societal regeneration being reduced to a promotion of a kind of safe and comfortable feel-good factor…..the X-factorisation of culture, if you like?: and the rejection or downplaying of the highbrow or complex – or of aspiration to being either of those things…..

(I think, like many things – and indeed the art/craft , the distinction makes more sense understood as a continuum, rather than a binary either-or, but I still think it is a purposeful and real distinction.)

[apologies for the slightly incoherent nature of some of these ramblings. Not sure quite how we got here from Dunblane, but still.]

#46 I don’t think we’re disagreeing here – there are many different reasons for wanting to buy posthumous releases, so they serve plenty of purposes. The posthumous hit compilation is valuable for being definitive, as you say. But the posthumous hits Kinitawowi objects to aren’t exactly that, are they? Those hits can happen before the definitive collections are compiled – they might be the most recent compilation (missing the artist’s more recent hits), or their most famous album, or (most relevant to Popular) one of their old songs becoming a posthumous hit single.

And in the case of singles, I really can’t see them being bought by people who already own the song; such hits must be driven by people who don’t, whether they were too young to hear it the first time round, or didn’t buy it first time round but have decided they like it, or bought it first time round but lost or disposed of it and now want it again. Whatever the reason, they don’t have the song, they want the song, they buy the song, it becomes a hit. I don’t see learning about an artist’s death as an inherently objectionable reason for wanting to buy a song or an album (or a book, or a DVD). On the contrary, the career retrospectives that follow an artist’s death can be a helpful guide to what’s worth getting. I’ve bought many singles and albums unheard just because a favourite living artist released them, and my strike rate with those has probably been a lot worse; I might even have helped a few dud albums to number one that way. (Sorry about that, punctum. )

Re 37: “our old loves are likely to linger in our mp3 libraries, because who has the time to weed them out…” I’ve got to the stage where I’m having to ‘weed them out’ because my laptop is starting to crawl to a snail’s pace. There’s not much stored in it apart from music. Rockabilly and Toytown Psych have now been heavily edited. Technology is failing me.

There have, of course, already been several Popular entries which were posthumous. That Eddie Cochran’s Three Steps To Heaven was his only number one, possibly as a ‘tribute’ soon after his death, doesn’t diminish the song’s worth, or make the reasons people bought it at the time “objectionable”. Forty-odd years on, few people other than pop nerds will know that it was a posthumous number one (or even that it was a number one, for that matter).

#48 No, I think we are largely agreeing, I was just raising an eye at the tying of “is a fan” with “owns a previously released single” – particularly for big popstars, there’s a lot of people in the first category but not the second. “a new audience hearing the music for the first time” – surely there can’t have been enough of these on the planet to fill a phonebox by the time of MJ’s death?

I am amused though by the fannish completion of the loop as regards exposure to music – the two highest level of fans being those who have heard the music for months before they buy it and those that have never heard a note.

#37/49 – of course there is also the tendency towards moving towards music as a service, Spotify being the big name, where simple curiousity can be answered without having to actually buy anything.